By Luis Meiners

Against the rise of a historical anti-racist rebellion in recent months, violent actions by far-right individuals and paramilitary groups have taken place in several cities of the United States. Among the most recent, the armed attack against a protest perpetrated by Kyle Rittenhouse (together with a paramilitary group), killing Anthony Huber and Joseph Rosenbaum stands out. Groups like “Blue Lives Matters” and other openly neo-fascists like the “Proud Boys” have called counter-demonstrations or mobilized to confront the protests.

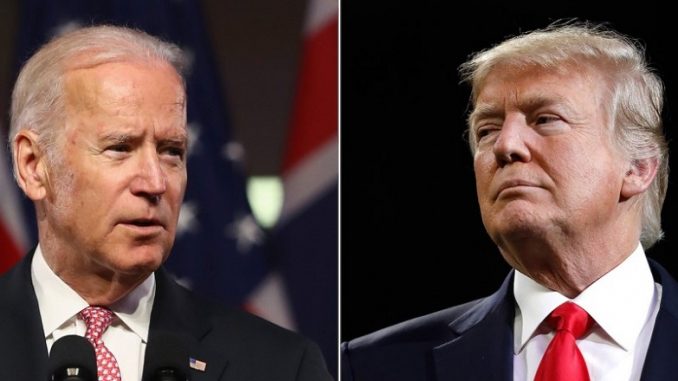

The fact that in these actions the support for Trump is explicit, and that he in turn encourages them through Twitter, added to his “Law and Order” discourse and the strongly repressive response against the protests, has generated logical debates around the characterization of his government and the politics of the left. Simultaneously, “progressive” sectors of the Democratic Party and the reformist left use the characterization of Trump as a fascist to argue the need to vote for Biden.

Starting from the shared goal of putting an end to authoritarianism, white supremacism and the extreme right, it must be said that the path proposed by the Democrats and their progressive allies will not lead in this direction. There are many historical examples of this. The question of fascism and how to confront it occupied a fundamental place in the debates and activity of the left in the interwar period. This article brings back some of those contributions for the debate on the tasks of the present.

What is fascism?

At the end of the First World War, much of Europe was in acute economic, social and political crisis. The Russian Revolution opened a period of revolutionary ascent that spread across the continent and beyond. The defeat of this ascent opened a period of counterrevolution marked by the rise of fascism, provoking important debates in the communist movement. An adequate characterization of the new phenomenon was essential to respond to the challenge it posed. Trotsky made some of his most important contributions to Marxist analysis and politics in this debate.

Possibly due to inexperience first, but then decidedly because of the orientation imposed on the Communist International by Stalinism, the leaderships of the communist parties did not see the specificities of fascism and tended to dilute it in the general characteristics of bourgeois reaction. Stalinism took this to its ultimate consequences, erasing the differences between fascism and social democracy, and arguing that Hitler’s rise would be the prelude to socialist revolution.

Trotsky, on the other hand, defined its specific features. For him, “the gist of fascism and its task consist in a complete suppression of all workers’ organizations and in the prevention of their revival. In a developed capitalist society this goal cannot be achieved by police methods alone. There is only one method for it, and that is directly opposing the pressure of the proletariat – the moment it weakens – by the pressure of the desperate masses of the petty bourgeoisie. It is this particular system of capitalist reaction that has entered history under the name of fascism. “[1]

The possibility for the bourgeoisie to mobilize the petty bourgeoisie to crush the proletariat and its organizations with methods of civil war, opens up from a specific combination of historical circumstances. In this regard, Trotsky pointed out: “fascism is each time the final link of a specific political cycle composed of the following: the gravest crisis of capitalist society; the growth of the radicalization of the working class; the growth of sympathy toward the working class and a yearning for change on the part of the rural and urban petty bourgeoisie; the extreme confusion of the big bourgeoisie; its cowardly and treacherous maneuvers aimed at avoiding the revolutionary climax; the exhaustion of the proletariat, growing confusion and indifference; the aggravation of the social crisis; the despair of the petty bourgeoisie, its yearning for change, the collective neurosis of the petty bourgeoisie, its readiness to believe in miracles; its readiness for violent measures; the growth of hostility towards the proletariat which has deceived its expectations. These are the premises for a swift formation of a fascist party and its victory.”[2] To this he adds that the proletariat is incapable of taking power not because of its own limitations, but fundamentally due to the vacillations and open betrayals of its Social Democratic and Stalinist leaderships.

Defining the new phenomenon with precision was key to giving an adequate response. Too broad a definition, which did not indicate the specific characteristics that differentiate fascism from other forms of bourgeois reaction, led to the minimization of the counterrevolutionary danger it represented. In the case of Stalinism, the policy of equating fascism even with social democracy, led it to reject the tactic of the united front to defeat it. Thus, opening the door to Hitler’s rise in Germany.

Trump and the extreme right

The presence of extreme right-wing groups and their violence has been constant throughout US history. However, it is clear that during the Trump presidency these groups have found sympathy and echo in the White House. Trump has contributed to broadening their audience, giving them legitimacy and making them more mainstream, helping to spread their conspiracy theories on Twitter and providing coverage for their violent actions. On his recent visit to Kenosha, Trump charged against the protests, defended security forces and implied that Kyle Rittenhouse acted in self-defense.

The presence of Trump in the White House is one of the conditions that contributes to the growth of these groups, but not the only one. Neither is it the main cause. On the contrary, the same deep, structural conditions that encourage the development of the extreme right, are part of the elements that explain Trump’s arrival to the presidency. The 2008 economic crisis dislocated the conditions of stability that had been eroded by decades of austerity policies. The result of this was a period of increasing social and political polarization. This paved the way for an “outsider” with a right-wing populist discourse.

Trump’s authoritarian, bonapartist style is also a reflection of the crisis of the traditional institutions of the bourgeois democratic regime: of congress, of the political parties, etc. He appears as a strong figure against “the swamp” of Washington. But these same institutions are still there. There has been no shift towards a fascist regime. Trump has not relied on a radicalized right-wing base to crush the working class with methods of civil war, wiping out formal bourgeois democracy in the way.

We must also incorporate the international dynamics into the analysis. In response to the depth of the capitalist crisis, the bourgeoisie tries to push further policies of austerity. To achieve this, it accentuates the bonapartist and authoritarian aspects of all regimes. Governments like Trump’s are clear expressions of this, but it is a general trend even among those who strive to present themselves as more democratic.

Imposing a fascist regime implies defeating the working class. It means liquidating their organizations, parties and unions, and their vanguard. In general, dismantling all the movements and organizations of all the oppressed sectors. And this entails destroying democratic institutions, however formal and limited they may be. In this sense, the Trump administration and the political regime of the US cannot be defined as fascist, even when there are pro-fascist groups in the most extreme sectors of its base.

Despite the growing polarization, what marks the dynamics of the political situation is the rise of the class struggle with the huge anti-racist rebellion. It is on this balance of class forces that we must root our analysis of the political situation and our politics.

The lesser evil against fascism?

If the development of fascist groups is the result of causes that cannot be reduced to Trump, his sole exit from the presidency is not going to stop this process. A central theme of the Democratic convention was “national unity” to defend democracy. Then Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez clearly argued that it is necessary to vote for Biden to defeat fascism. On this question, historical experience can again serve to obtain lessons for the present.

After its disastrous policy that allowed the rise of Nazism, Stalinism took a new sharp turn and called for the formation of fronts with the “democratic” bourgeois parties to stop fascism from coming to power. The policy of the “popular front” implied stopping the revolutionary impulse of the masses in the face of the crisis. The communist and socialist parties preached prudence, containing the demands for structural change so as not to antagonize their allies from the bourgeois parties.

In a scenario of crisis and rapid decomposition of bourgeois society, such as that of the 1930s, avoiding structural change quickly translates into sustaining conditions of misery and pauperization, not only for the working class but also for broad layers of the middle class and the petty bourgeoisie. Thus, exacerbating the conditions that make the emergence and consolidation of fascism possible.

Furthermore, the politics of the popular front not only sustained the structural conditions of crisis, but also created the political conditions for fascism to grow. The working class is demoralized when it sees that the government which its parties integrate does not produce the changes they demand. At the same time these leaderships call them to calm. The petty bourgeoisie hit by the crisis, in the face of the retreat of the proletariat, turns towards order. And thus “the party of counterrevolutionary despair” (L. Trotsky) is strengthened.

We can draw some parallels with the current situation, which allow us to analyze the politics of lesser evilism. The pandemic has qualitatively exacerbated the social crisis. There has been an abrupt change in the living conditions of millions. This has strongly affected the working class, but also sectors of the petty bourgeoisie such as small business owners who saw their sources of income suddenly cut off, with the prospect of an uncertain future.

Within this framework, there has been a rise in the class struggle, which has taken a qualitative leap with the rebellion against systemic racism and police violence. Simultaneously, although much smaller in magnitude, there have also been street expressions of the extreme right, such as the demonstrations against the quarantine in April / May and those organized in response to the rebellion.

Trump continues to polarize, hardening his right-wing speech. He bets on stirring up his base to have a chance in November. Biden and the Democratic Party seek to contain social mobilization, arguing, along with the mass media, that the protests fuel Trump’s electoral possibilities. This combination can create the feeling that it is the right wing that has the initiative.

A Biden victory will not change the structural conditions that feed the far right. Wall Street knows well that his administration will not do anything that affects its interests, rewarding him with its support. For the left, closing ranks behind Biden and the Democrats means continuing to postpone the urgent task of building an independent socialist party.

With Trump or Biden, the prospect is for

the crisis to deepen, and there will be a greater rise in the class struggle

and a wave of radicalization. That will be the key moment that will put the

socialist left to the test. Without an independent party, the left will have

its hands tied to intervene, and will contribute to a scenario of regression

and demoralization. The consequences of this are known. Therefore, to defeat

any prospect of fascism, the most urgent task isn’t voting for Biden, but

building an independent socialist party.

[1] Trotsky, León (1932). What next? Vital questions for the German proletariat.

[2] Trotsky, Leon (1940): Bonapartism, fascism and war.