By German Gómez

January 1929 was already beginning to show signs of the exhaustion of capitalist production, which would explode in October of that same year resulting in the so-called “great depression,” which would affect the world economically and socially, but specially the United States. Also in that January, one of the most emblematic figures of the struggle for the civil rights of African Americans in the United States, the Reverend Martin Luther King, would be born. This January 15 marks the 92nd anniversary of his birth, we remember his struggle and his time.

In December 1955, an African-American woman, Rosa Parks, refused to give up the seat reserved for white people on a bus, generating a scandal that would end up in the media. With that small act of resistance, a new upswing in the struggles that African Americans had been pushing for almost 90 years since the end of the Civil War began. In that rise, one of the most recognized figures with greater political weight would be the Reverend of the Baptist Church, Martin Luther King. The irruption of his figure in the political scene would emerge with the organization of a boycott against passenger transportation companies in Montgomery, Alabama. The boycott was successful, the Supreme Court forced the complete elimination of segregation in transportation, but at the same time it was a symbolic success because it was achieved in the heart of the Confederate South.

The Reverend, who followed in his father’s footsteps since he was a child, becoming a preacher, used to mix religious readings with readings about the reality suffered by his people. He found a religious explanation for the injustices, but also one of action, making the attendance of his church grow exponentially and being a respected reference for the communities of the south, deeply exploited as well as deeply religious. His charisma was evident and would be a fundamental part of his political life.

King was considered one of the most important representatives of African Americans, because he combined a series of factors that made him attractive to the masses and the media. On the one hand, his “pacifist” position, which he exploited by condemning the violence suffered by the African-American people, but at the same time he fought for peaceful resistance, like Mahatma Gandhi [1], whom he used to mark as an example. On the other hand, his great oratory produced those speeches that lasted for hours and could be heard by thousands without losing attention. He was also seen with sympathy by a large white sector, because he did not fundamentally question the capitalist system, or the “American way of life” [2], but demanded equal participation of the population, regardless of their color, he spoke of a capitalism for all, closer to social democratic ideas.

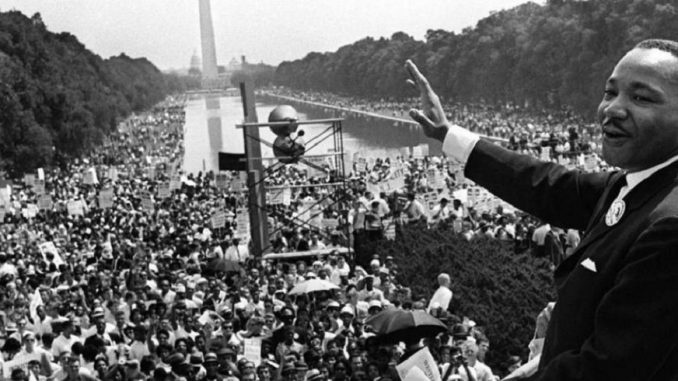

The growth of King’s figure would have its maximum expression in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. This was not a march organized with a concrete program, since a group of organizers supported President Kennedy’s agenda while others were going to denounce him. What was clear was that the mobilizing power of the civil rights movement was at its peak. Before nearly 300,000 people gathered, King gave his most famous speech, known as “I Have a Dream,”[3] in which he proposed as an expression of desire a society where whites and blacks could live harmoniously as equals. This speech would be one of the greatest declarations at the beginning of that era. It earned him the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize.

The other cheek or the other fist?

However, it was not King’s figure and his political position that monopolized his rise.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, there already were organizations that fought for the rights of people of color and against the abuses they constantly suffered. The most recognized was the NAACP[4] (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) founded by William Edward Du Bois, one of the fathers of the organized political struggle of African Americans, which held a program oriented towards “To promote equal rights and to eradicate caste and race prejudice among the citizens of the United States, to advance regarding the interests of citizens of color, to secure for them a fair vote, and to increase their opportunities to secure justice in the courts, education for children, employment to the best of their ability, and full equality before the law.”

On the other side was Jamaican Marcus Garvey, who upheld the idea of a “return to Africa” and proposed that all the descendants of slaves be moved back to their original continent, even proposing to create a “black” sea line, the Black Star Line, to achieve his goal [6].

This divergence between being part or leaving, between pacifism and violence was never settled. While Reverend King supported pacifism and integrationism, there were other figures who argued the opposite and disputed the leadership of the masses. The most relevant was Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little) who belonged to the “nation of Islam,” a religious and political grouping that argued that the answer to the violence suffered was to defend itself with the same violence, that in white America there would never be a place for blacks and that it supported the construction of a nation of its own within the United States. They were taking up the old debates of Garvey and Du Bois.

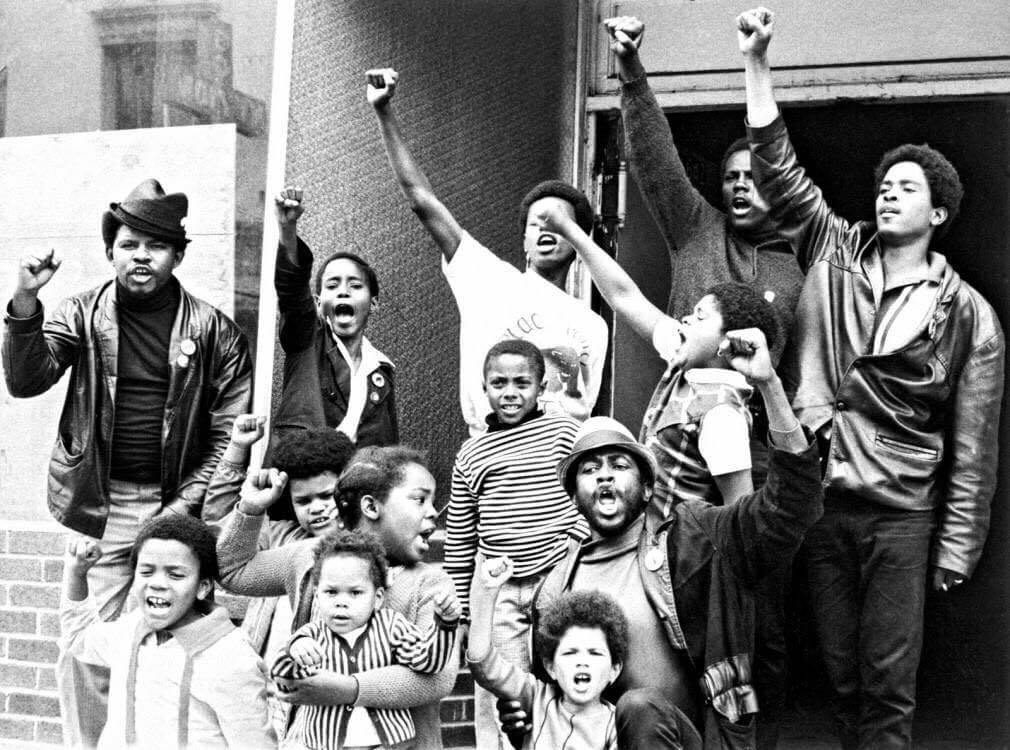

However, by 1965, along with the emergence of the youth as a whole against the Vietnam War, a sector more linked to this movement would also appear, including the ideas of “Black Power”[7], the struggle put forward by Malcolm X, but also the political dispute embodied in the ideas of Marx and Che Guevara, the Black Panther party of Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. Originally they began by carrying out self-defense activities (above all against police abuse) but they gradually extended to social and territorial actions. By 1970 the Black Panthers were a political organization with a strong youth component that linked racial and class issues. This put it in the sights of the FBI, which began a series of counterintelligence operations (COINTELPRO)[8] to discredit the organization in the eyes of public opinion. These actions were effective and made the party practically extinct by 1972.

Advances and setbacks

The struggle led by Luther King, Malcolm X and many others payed off in 1965, a decade after Rosa Parks’ contempt, when finally, with the drafting of the new Civil Rights Act, racial segregation[9] was ended and all remaining “Jim Crow” laws[10] were repealed. For the first time since the end of the Civil War, all the inhabitants of the country were granted citizenship status without any kind of racial distinction. The movement for the civil rights of racial minorities seemed to be able to start taking on the other political tasks of their class, but the bourgeoisie was not going to let them go any further.

On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King was killed by a white racist while supporting a garbage collector’s strike in Memphis, Tennessee. This was another act of the social reaction of the most conservative and rotten sectors that had already claimed the life of Malcolm X in 1965 and of other leaders throughout the decade. The struggle that King and so many others had carried out had given a new range of possibilities to people of color, but the end of segregation did not guarantee that access to these rights would be simple.

The 1960s and the figure of Martin Luther King were one of the high points in the struggle of African-American people, where they were able to finally defeat segregation, but at the same time they continued to confront the systemic racism of American capitalism. During the 1970s and especially after the 1973 oil crisis, unemployment and social crisis would hit the African-American population even harder. Despite being legally equal, the system’s role was to be the fuse to politically atone for the crises. Freedom still found one more obstacle, capitalism and its austerity measures against the workers.

1] Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948), the Indian leader who led the struggle for his country’s independence and used the method of “peaceful resistance” which consisted of remaining unmoved by repression.

2] A name used to describe the consumerist stereotype of the American family, propagandistically used against the USSR during the Cold War.

3] “I have a Dream,” complete speech on the page of the Spanish newspaper El Mundo.

4] The NAACP was made up of both African-American and Caucasian citizens, who fought for the integration of both ethnic groups.

5] 1st Congress of the NAACP, letter to the citizens May 30, 1911.

6] Garvey’s ideas were based on the experience of the African country known as Liberia, which began as a U.S. colony in Africa and was a safe haven for thousands of freedmen prior to the civil war.

7] Black Power was a social, cultural and artistic movement that focused on the appreciation of African culture, and the revaluation of the customs of slave ancestors.

8] COINTELPRO (Counter-Intelligence Propaganda) was an FBI program that developed by infiltrating leftist or “dangerous” organizations in order to produce alien acts but claiming to discredit them in the eyes of public opinion.

9] Segregation refers to the policy of “equal but separate” that offered lower quality services to the African-American population.

10] Jim Crow was the popular name for racial segregation laws.