By Camilo Parada, Movimiento Anticapitalista

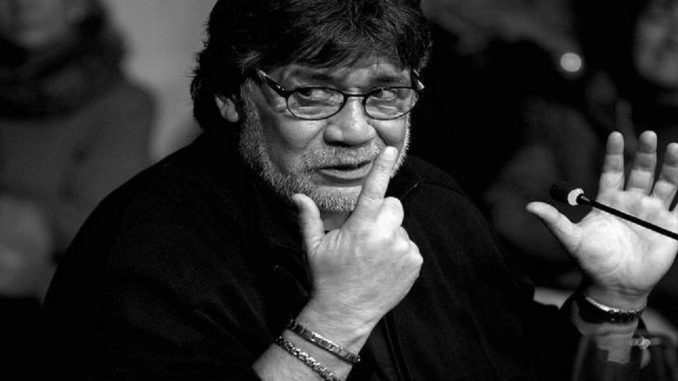

Internationalism is mourning. Luis Sepúlveda has left us. He was a Chilean writer, journalist, filmmaker, but above all, a committed anti-capitalist fighter who defended one of the great proletarian principles: internationalist solidarity.

Luis had said of himself that he was born “red, deeply red”. From an early age, he developed strong political and social concerns, becoming a militant at the age of fifteen in La Jota, the Communist Youth of Chile. But he was expelled in the midst of the upheavals of 1968 and joined the fraction of the Socialist Party known as the National Liberation Army. He studied theater at the University of Chile, where he graduated as director and then finished a Communication Sciences career at the University of Heidelberg, Germany.

For Luis, writing was an act of resistance, a resistance that accompanied him without a doubt until the morning of April 16, 2020, when he died at the age of 70, after a struggle against COVID-19 in Oviedo, his city of residence since 1996. Resistance is an integral part of the essence of the Chilean writer, an active opponent of Pinochet’s bloody capitalist dictatorship. The tyrant sentenced him to two and a half years in prison, which was commuted to house arrest thanks to international pressure, specifically the constant insistence of the German section of Amnesty International. Once his sentence was completed, Luis went underground, but again the repressive apparatuses of the dictatorial regime surrounded him, so he had to go into an exile that took him to different countries in South America. After an intense journey, he arrived in Ecuador, where he focused on his dramatic arts work and collaborated with Unesco in a program to protect the indigenous peoples of the Amazon, where The Old Man Who Read Love Novels was forged.

It was during his Ecuadorian exile that – moved by his internationalist concerns – he joined the Simón Bolívar Internationalist Brigade as a volunteer in 1979. This brigade was promoted by the Socialist Workers Party (PST) of Colombia, of the international current led by Argentine revolutionary Nahuel Moreno to fight in the Nicaraguan revolution, but was later expelled from Nicaragua by the Ortega Sandinista government and handed over to General Torrijos in Panama, where its members were victims of severe torture. Nahuel Moreno expressed at that time the causes of the expulsion: “Specifically, as reported in the world press, the Brigade was expelled for: 1. Organizing unions (about 80) through democratic workers’ assemblies; 2. Promoting the land occupations by dispossessed peasants; 3. Promoting the organization of popular militias and 4. Denouncing some members of the Governing Junta as bourgeois.”[1]

In 1980 Sepúlveda obtained political asylum in Germany, where he lived for over 10 years in Hamburg, a city in which he actively collaborated with Greenpeace and worked as a correspondent for Der Spiegel. Luis lived in the nineties between Germany and France. In 1997 he sttled in Gijón, in the autonomous community of Asturias, where he founded the Gijón Ibero-American Book Fair.

At the end of February of this year, he was infected with COVID-19 while he was at a literature festival in Portugal, he returned to Asturias where he was hospitalized in Oviedo until this morning, when he died. We internationalists will honor your memory.

Works

- Chronicle of Pedro Nadie (1969)

- Fears, lives, deaths and other hallucinations

- Travel Notebook (1986)

- Boykott

- An old man who read love novels (1988)

- Disencounter on the other side of time (La Felguera Short Story Prize, 1990)

- Patagonia Express (1995)

- Komplot: First part of an irresponsible anthology (Editorial Joaquín Mortiz, México D.F., 1995)

- Name of a bullfighter (novel, Tusquets, Barcelona, 1994)

- World at the end of the world (Tusquets, Barcelona, 1996)

- Story of a seagull and the cat that taught him to fly (Tusquets, Barcelona, 1996)

- Disencounters (Tusquets, Barcelona, 1997)

- The game of intrigue, (with Martín Casariego, Javier García Sánchez and Paco Ignacio Taibo II, Espasa, 1997)

- Diary of a sentimental killer & Yacaré (Tusquets, Barcelona, 1998)

- Marginal stories (Seix Barral, Barcelona, 2000)

- Hot Line (Ediciones B, Barcelona, 2002)

- Pinochet’s Madness (20 articles, We Still Believe in Dreams, Santiago de Chile, 2002)

- Cheers, Professor Gálvez! and other stories (Ediciones de la Banda Oriental, Montevideo, 2004)

- The worst tales of the Brothers Grimm (novel co-authored with the Uruguayan writer Mario Delgado Aparaín, Roca Editorial, Barcelona, 2004 and Seix Barral, Buenos Aires, 2004)

- To narrate is to resist, conversations with Bruno Arpaia

- Moleskine, notes and reflections (articles, Ediciones B, Barcelona, 2004)

- The power of dreams (articles, We Still Believe in Dreams, Santiago de Chile, 2004)

- Carolina Huechuraba’s underpants (17 chronicles, We Still Believe in Dreams, Santiago de Chile, 2006)

- Life, passion and death of the Fat and the Skinny (radio script, 2007)

- Aladdin’s Lamp (Tusquets, Barcelona, 2008)

- The shadow of what we were (Espasa, 2009)

- Stories from here and there (Belacqva, 2010)

- Latest news from the South (travel book; with photos by Daniel Mordzinski, Espasa, Barcelona, 2011; La Banda Oriental, Montevideo, 2011; Ediciones de La Flor, Buenos Aires, 2011)

- History of Max, Mix and Mex (story with illustrations by Noemí Villamuza; Espasa, Barcelona, 2012)

- Marginal Stories II

- An Idea of Happiness (with Carlo Petrini, Guanda, Italy 2014)

- A Story I must tell (articles, Editorial Still Believe in Dreams, Chile, 2014)

- Tutti i Racconti. (How many complete compiled by Bruno Arpaia, Guanda, Italy 2014)

- The Mute Uzbek

- Story of a Dog named Leal (Tusquets Editores, 2016)

- The End of History (Tusquets, 2017)

- Story of a snail that discovered the importance of slowness (Tusquets Editores, 2018)

- Story of a white whale (Tusquets Editores, 2019)

Awards and distinctions

- 1976, Gabriela Mistral Poetry Prize.

- 1985, Ciudad Alcalá de Henares Prize for Travel Notebook.

- 1988, Tigre Juan Award, for An old man who read love novels.

- 1992, France Culture Etrangêre Award, for An old man who read love novels.

- 1992, Relais H d’Roman Award for Evasion, for An Old Man Who Read Love Novels.

- 1994, International Ennio Flaiano Prize.

- 1996, International Grinzane Cavour Award.

- 1996, Ovid International Prize.

- 1997, Terra Prize.

- 2001, Critics Award, Chile.

- 2009, Spring Novel Award

- 2013, Nordsud Pescarabruzzo Award.

- 2013, Pegaso Gold Award. Florence, Italy.

- 2014, Taormina Prize for Literary Excellence.

- 2014, Vigevano Prize for literary career.

- 2014, Chiara Prize for Literary Career. Italy.

- 2016, Eduardo Lourenzo Award.

- Knight of Arts and Letters of the French Republic.

- Doctor Honoris Causa from the University of Toulon. France.

- Doctor Honoris Causa from the University of Urbino. Italy.

[1] Moreno, Nahuel (1982). Escuela de cuadros.