Por Alternativa Anticapitalista – Nicaragua

Han pasado 41 años desde el triunfo de la revolución popular nicaraguense del 19 de julio de 1979. La revolución nos demostró que la fuerza de los pueblos en Nicaragua es tan potente que puede sacarse a un dictador terrorista de encima, pero que la lucha debe ir más allá hasta cambiar la base misma del régimen y sus instituciones.[1]

La revolución popular del 79*

Las expectativas de la revolución eran gigantescas, masivas. Nicaragua tenía todo por ganar. Amplias capas trabajadoras, campesinas y juveniles derrocaron la dinastía Somocista, y con su lucha heroica defendieron el sueño de una Nicaragua libre para todos. Paradójicamente, el mayor responsable de la traición a esta victoria es el Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, que con sus políticas antidemocráticas hicieron retroceder las conquistas populares para mantener intacto el sistema capitalista en la región, el Frente que gobernó en los años 80s y que regresó en 2006 para mutar en otra dictadura. Fue esta dirección, que traicionó la revolución y los intereses de la sociedad en su conjunto. Nos traicionaron.

Este es el primero de tres artículos, en el marco de esta fecha histórica para Nicaragua y el mundo. Compartimos algunas de las razones por las que cuestionamos el falso socialismo del FSLN.

El curso de una mutación

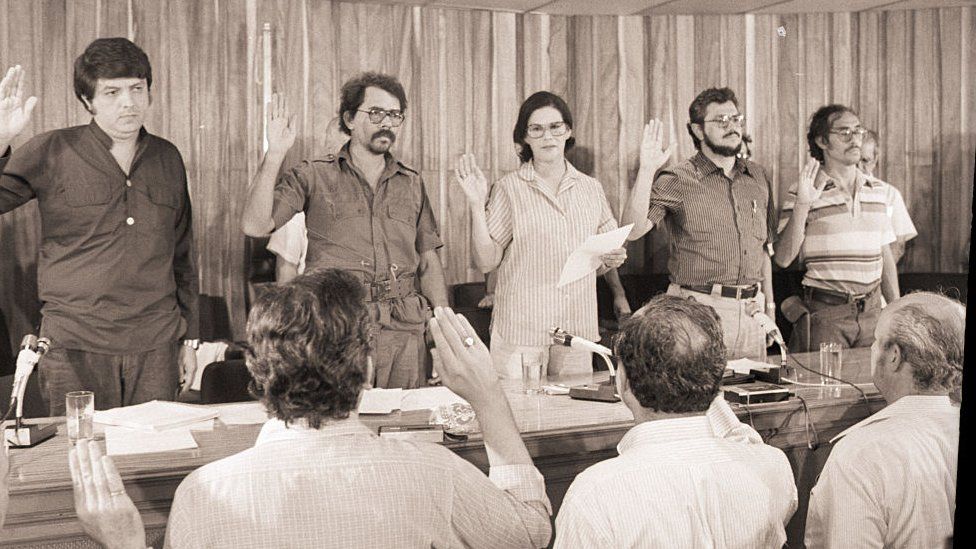

Un día después del triunfo de la revolución se instaló la Junta de Gobierno, fungía como Poder Ejecutivo y Administrativo, conformada por: Daniel Ortega, Sergio Ramírez y Moisés Hassan; Violeta Barrios de Chamorro y Alfonso Robelo, pro-estadounidenses y empresario.

Esta Junta compartía funciones legislativas con un Consejo de Estado tenía más de 30 miembros. Estaba conformada por 6 integrantes del FSLN, 6 miembros del Consejo Superior de la Empresa Privada (COSEP); representantes de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua (UNAN), todo tipo de partidos políticos y agrupaciones sindicales; ¡hasta el clero tenía silla! [1][2]; fue una coalición “antisomocista” entre la dirección del FSLN, la empresa privada, partidos tradicionales y la iglesia. ¡No fue un gobierno obrero![2]

Los socialista afirmamos que el poder debe residir en el pueblo y la sociedad en su conjunto y para avanzar a la revolución socialista, las armas deben estar en manos de la población bajo control democrático de sus organizaciones.

Daniel Ortega comentó el 31 de Julio en Barricada: “Por eso el FSLN que en los primeros días se hizo cargo del país, hoy está en proceso de entregar a la Junta todo el aparato administrativo y gubernamental y la Junta ha ido avanzando rápidamente en ese sentido, mientras que por su parte el FSLN adelanta pasos en la conformación y consolidación del nuevo ejército”[3].

Bajo esta lógica, se “derogó todo el sistema jurídico legal que los regían y dispuso la sustitución de la GN (la Guardia Nacional somocista) por un nuevo Ejército Nacional de carácter patriótico.”[4] Lo que se dispuso fue la creación de un ejército regular burgués, -que defiende los intereses de clase de su dirección, y del Estado-, y para lograrlo, desarmaron las milicias populares en especial la de los sindicatos combativos, críticos e independientes a la dirección del Frente. Es decir, desarmaron al pueblo y con esto consolidan otro golpe a la revolución.

Para que un gobierno sea socialista, debe ser un gobierno dirigido por las clases trabajadoras organizadas, creado a partir de organizaciones de bases y populares bajo la más amplia participación democrática en la planificación y toma de decisiones de lo político, lo económico y lo social; esto deviene en un nuevo tipo de estado diferente al estado burgués actual: un estado obrero y de transición.**

Los motores de la economía se los quedó la burguesía[3]

En el ámbito económico, los socialistas planteamos que la economía debe planificarse democráticamente con la participación de los trabajadores, los campesinos y el pueblo, para que tengan bajo su control los principales motores de la economía y se produzca en base a las necesidades reales de la población.

Lo que hizo el FSLN fue todo lo contrario: desde el inicio, pactó con la burguesía nacional e internacional y a esto le llamó Economía Mixta. Su enfoque: productivista. Por eso “no quiere decir que se haya terminado con la gran propiedad terrateniente. Entre otras muchas, permanece en manos privadas, por ejemplo, el ingenio San Antonio, el más grande del país. Esto es así porque son las masas, no el sandinismo, la vanguardia de la revolución agraria. Este último (el sandinismo) marcha detrás, y a regañadientes, de la movilización campesina.”[5]Los capitales transnacionales no quedaron por fuera de la partida. “Queremos decirles a los inversionistas de los EE.UU. que nuestro país no les ha cerrado las puertas…” invitaba con entusiasmo Daniel Ortega (Barricada, 7 de agosto 1979). Así la reforma agraria para darle la tierra a quien la trabaja, la habita y protege ancestralmente, no se concretó.

Maza y Cuello observan que “Esta situación ha dejado en poder directo de la burguesía el 60 por ciento del producto bruto interno, lo que implica el 81 por ciento de la producción agropecuaria, el 75 por ciento de la manufacturera, el 30 por ciento de la construcción y el 80 por ciento del comercio interior mayorista”[6]. En otras palabras los pobres, más pobres, y los ricos -y los nuevos ricos-, más ricos. Así el proceso de revolución tuvo pocos cambios revolucionarios.

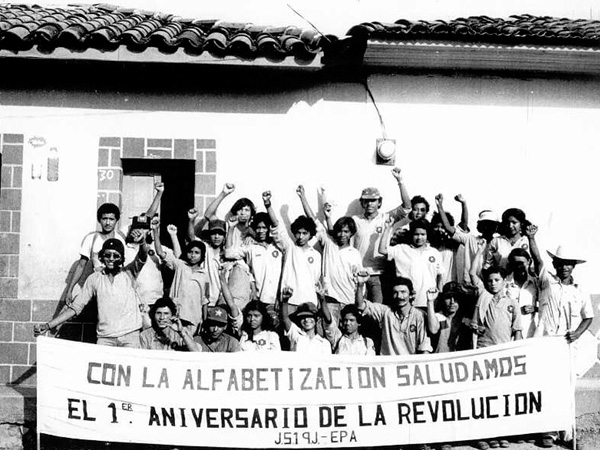

Como si fuera poco, los agravios se extendieron hasta los pueblos de la Mosquitia / Costa Caribe Nicaragüense. La Cruzada Nacional de Alfabetización, -salvaguardando la invaluable entrega revolucionaria de las juventudes que participaron y sus logros-, que fueron aprovechadas por el gobierno para sentar las bases de sus políticas extractivistas, el intento de aniquilar sus idiomas y sus epistemes (imponiendo el castellano); y sus desplazamientos forzados. El avance de la frontera agrícola, actividad voraz y depredadora no se detuvo en aquel entonces y continúa en la actualidad.

La revolución será internacionalista o no será

Los años ´70 y los ´80 fueron tiempos de ascensos revolucionarios en Centroamérica. La derrota del Somocismo a manos de la población nicaragüenses trajo esperanzas de cambio a la región y al mundo; sin embargo, la dirección del FSLN y el Partido Comunista Cubano tenían otros planes. Fidel Castro el 26 de julio de 1979 exclamaba que “alas afirmaciones o los temores expresados por alguna gente, de que si Nicaragua se iba a convertir en una nueva Cuba, los nicaragüenses le han dado una magnífica respuesta: ¡no, Nicaragua se va a convertir en una nueva Nicaragua! que es una cosa muy distinta.”[7] Esto marcó la política internacional sandinista para con los pueblos centroamericanos en lucha. El FSLN nunca se dispuso integralmente a apoyar a quienes combatían a sus propias dictaduras en la región; al contrario, les dio la espalda.

El #CasoJesuita es un juicio contra crímenes de lesa humanidad[8]. Un operativo militar, del batallón Atlacatl, contra la Universidad Centroamericana de El Salvador, el 16 de noviembre de 1989, dejó un saldo trágico de 8 muertes, “los mártires de la UCA”. Los testigos vinculan al entonces presidente Alfredo Cristiani, quien asumió la presidencia cuando Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional, FMLN, se encontraba a la ofensiva, y un alzamiento popular se vaticinaba. En ese entonces, Daniel Ortega firmó varios tratados para apoyar el desarme de los combatientes Centroamericanos. Les dio la espalda a las y los revolucionarios en El Salvador. Meses antes del atentado terrorista contra los jesuitas, el 8 de agosto, Ortega firmaba el Acuerdo de Tola y ratificaba “la excitativa a los grupos armados de la región en especial al FMLN, que aún persisten en la vía de la fuerza, a desistir de tales acciones.”[9]. Y casi un mes después del crimen en la administración de Cristiani, el 12 de diciembre, Ortega firmaría en Costa Rica “su más enérgica condena a las acciones armadas y de terrorismo que realizan las fuerzas irregulares en la región” y, para dejarlo claro, también su “apoyo decidido al Presidente de El Salvador, don Alfredo Cristiani y a su Gobierno.”[10]

El FSLN, la JGRN y el Gobierno de Reconstrucción Nacional siguieron al pie de la letra la exhortación de Castro y del imperialismo[11]: Detener la revolución centroamericana. Ni El Salvador, ni ningún otro país centroamericano se convertirían tampoco en una nueva Nicaragua. Los jefes del FSLN en Nicaragua contribuyeron para frenar el alzamiento revolucionario de toda la región; pactaron con los grandes capitales nacionales, regionales e internacionales, y con sus gobiernos de turno. No avanzaron con las tareas del socialismo: ni expropiaron a la burguesía, ni impulsaron la planificación democrática de la economía, ni extendieron la revolución en Centroamérica.

Los socialistas reconocemos que el capitalismo y sus instituciones son un sistema internacional de alcance global y por tanto hay que responder y organizar la revolución a ese mismo nivel. Por su parte, el estalinismo sostuvo que era posible construir el socialismo en un solo país, groso error, pues se demostró con amplia experiencia que lo que no avanza retrocede.

Internacionalismo militante: La Brigada Simón Bolívar[5]

“Necesítase gente. En la calle 17 4-49, oficina 201, de Bogotá, están necesitando gente. No dan trabajo ni prometen enriquecer aspirantes de la noche a la mañana a través de la venta de enciclopedias. Lo único que ofrecen es la posibilidad de perder la vida, sometiéndose a riesgos e incomodidades y llevar durante un tiempo incierto una vida llena de peligros. A cambio solo brindan la oportunidad de luchar por la liberación de un pueblo. En este lugar funciona la oficina de reclutamiento de combatientes colombianos que quieran voluntariamente alistarse en la lucha armada contra la dictadura de Anastasio Somoza en Nicaragua”[12] así publicó Daniel Samper Pizano en mayo de 1979 en su columna del periódico colombiano El Tiempo.

Previo a eso, la corriente trotskista orientada por Nahuel Moreno convocó en Colombia a la conformación de la Brigada Simón Bolívar, BSB, en similitud de las brigadas internacionalistas surgidas durante la guerra civil española, que funcionaban independientes a los aparatos beligerantes.

Miles se anotaron en las planillas de la oficina 201, otros miles se organizaban en todas las latitudes del globo. Las campañas financieras para proveer a la brigada las hubo de todo tipo, desde ventas de bonos sandinistas, hasta conciertos de solidaridad. De 10 en 10 llegaron a Nicaragua. Combatieron en el Frente Sur y Bluefields, e instalaron allí un primer gobierno una vez que liberaron la ciudad. Reubicados en Managua por la Junta, se dieron la tarea de organizar sindicatos combativos con sus milicias independientes y críticas al FSLN. Conformaron más de 100 sindicatos, que luego formarían la Central Sandinista de Trabajadores (CST).

“La primera manifestación obrera de Nicaragua fue realizada por los sindicatos formados por la BSB el día 14 de agosto. Según la revista Time participaron 3.000 proletarios fabriles planteando el pago de los salarios caídos y el alto a los despidos. En esta movilización, además, participaron delegaciones de los CDS y de las milicias para entregar al GRN y al FSLN miles de firmas pidiendo la nacionalidad nicaragüense para los extranjeros de la BSB. De esta manera se pedía dar marcha atrás a la política de echar del país a los internacionalistas de la Brigada o suspender sus actividades (sic.)”[13]. Por su posición crítica y su política de independencia programática, “la Brigada Simón Bolívar, que además planteaba la extensión de la lucha hacia El Salvador, fue expulsada del país (a Panamá, en colaboración con el dictador Torrijos) y los militantes trotskistas fueron perseguidos.”[14]

La BSB planteó una ruta: la organización popular independientes de burócratas y empresarios para impulsar un programa socialista para Nicaragua y Centroamérica. La comandancia del FSLN no aceptó que las brigadas tuvieran independencia política y organizativa, intervino a los sindicatos, los burocratizó a través la CST y expulsó a la BSB de Nicaragua hacia la cruel dictadura panameña que les torturó. Esta experiencia de la BSB evidenció la política antidemocrática y de conciliación de clases y que la dirección del FSLN es una burocracia.

El pueblo en rebeldía lo da todo, la dirección traidora falla.[6]

Tenemos 41 años sabiendo que podemos derrocar dictadores y que la revolución del ´79 forjada con la organización y lucha de miles de niños y jóvenes y del pueblo nicaragüenses pudo ser de otra manera, pero que después del triunfo se mantuvo el régimen anterior y no se avanzó en la totalidad del rumbo revolucionario, si llegó la “democracia” aunque burguesa. Hoy habiéndose deformado tanto este hito de la lucha de clases en Nicaragua, es comprensible el desencanto que provocó la degeneración de esa “nueva Nicaragua” a manos de una dirección burocrática, antidemocrática, que reconstruyó el Estado burgués para mantener el capitalismo y sostener el “viejo”.

El FSLN se quedó a medias en la tarea de redefinir todo y crear un Estado realmente revolucionario para las mayorías, y en ese sentido las generaciones nacidas después de los 80´s crecimos con traumas, pérdidas familiares, silencios y duelos sociales que no hemos logrado superar en conjunto, porque ni siquiera hay políticas de memoria para sanar colectivamente estos episodios históricos que de alguna manera se vuelven a repetir hoy. Nuestras familias se sienten traicionadas y desencantadas, pero no abandonaron nunca su sentido de justicia social y dignidad para todos, por eso es importante no abandonar esta perspectiva y resignificar las tareas que quedaron pendientes.

La principal conclusión es que faltó y hace falta una dirección revolucionaria en nuestro país, que quiera romper con los poderes de facto, el empresariado criollo y transnacional, y empoderar a la sociedad en su conjunto para que seamos artífices de nuestro propio destino. Una dirección que luche por un gobierno de quienes nunca hemos gobernado: la clase trabajadora, las juventudes, las mujeres, los pueblos originarios y afrodescendientes, no es utopía sino necesidad urgente.

Desde acá queremos impulsar estos procesos de reflexión y discusión política colectiva, y la urgencia de construir una alternativa política anticapitalista, feminista, ecosocialista e internacionalista para dar vuelta a todo en Nicaragua y Centroamérica. Esa es nuestra estrategia y te invitamos a ser parte.

*Este artículo es el primero de una serie de tres donde analizamos el rol de la dirección sandinista en tres períodos, caracterizando cada uno para problematizar sobre su falso “socialismo”. Nuestro próximo artículo, se referirá a su rol como partido de oposición en la década de los 90s.

**El Estado Obrero y Transitorio es, en todo caso, una

conquista parcial de la revolución C.A y mundial. En concreto es la

consolidación de una clase política (trabajadora y campesina e indígena) en la

construcción de una superestructura para la movilización permanente que

extienda y profundice la revolución a escala regional. Nuestro objetivo no es

un estado obrero nacional, sino la creación de condiciones para nuevas formas

de relación social, sin explotación de clases y transitar a la abolición del

Estado.

[1]http://legislacion.asamblea.gob.ni/normaweb.nsf/9e314815a08d4a6206257265005d21f9/1a224f38057e9dc5062573080055c4de?OpenDocument

[2]http://legislacion.asamblea.gob.ni/normaweb.nsf/($All)/1DF920F2FD1A0B40062570A10057BF21?OpenDocument

[3] Nicaragua: ¿reforma o revolución? Recopilación de artículos y documentos; Tomo I; Carlos Vig; Bogotá; 1980; p. 38.

[4] https://www.ejercito.mil.ni/contenido/ejercito/historia/historia-fundacion-eps.html

[5] El Sandinismo y la Revolución Nicaragüense, Nahuel Moreno; Buenos Aires; 2018; p. 6.

[6] Cuello, H. F. y Maza, J., Nicaragua: la revolución congelada, Bogotá, 1982; p. 14.

[7] http://www.cuba.cu/gobierno/discursos/1979/esp/f260779e.html

[8]https://elfaro.net/es/202007/el_salvador/24623/Juicio-jesuitas-Testigos-vinculan-a-Cristiani-Parker-y-agentes-del-FBI.htm

[9] Resoluciones de los presidentes centroamericanos Acuerdos de Tela, Quinta cumbre de presidentes centroamericanos, Puerto Tela, Honduras, 7 de Agosto de 1989.

Puerto Tela, Honduras, 7 de Agosto de 1989.

[10] Declaración de San Isidro de Coronado; Sexta cumbre de presidentes centroamericanos; San Isidro Coronado, Costa Rica 12 de Diciembre de 1989.

[11] https://www.cidh.oas.org/countryrep/Nicaragua81sp/introduccion.htm

[12]Cita a Daniel Samper Pizano, El Tiempo, Colombia, mayo de 1979, en https://contrahegemoniaweb.com.ar/2019/08/01/nora-ciapponi-en-la-brigada-simon-bolivar-parte-i/

[13] Nicaragua: ¿reforma o revolución? Recopilación de artículos y documentos; Tomo II; Carlos Vig; Bogotá; 1980; p. 528.

[14] Cuello, H. F. y Maza, J., Nicaragua: la revolución congelada, Bogotá, 1982;p. 16.