On September 4, 1970, the Popular Unity won the presidential elections. Their victory awakened enormous expectations and put to the test the theory of the “peaceful road to socialism” advocated by the Socialist Party and the Communist Party. Three years later the coup led by Pinochet tragically ended that experience. Drawing conclusions from this process at a time when the Chilean masses are once again in check against the regime inherited from Pinochet and a workers’ and popular upsurge is of great importance for those of us who are fighting to end the capitalist system.

By Emilio Poliak

The 1960s was marked in Latin America by the radicalization of important sectors of the mass movement following the triumph of the Cuban Revolution and by the rise of the French May, the Cordobazo and other important struggles around the world. The 1970 elections took place in this context and with a rise that had been growing in Chile since 1967 as a response to the economic deterioration and the repression of the Christian Democrat government.

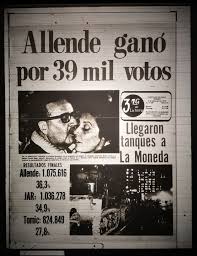

In this context, the bourgeoisie was divided between the National Party and Christian Democracy in the face of the presidential elections, facilitating the victory of the Popular Unity. The leading forces of this coalition were the Socialist Party and the Communist Party, and it also included bourgeois parties like the Radical Party and the MAPU (rupture of the DC). Salvador Allende obtained 36.3%, surpassing Jorge Alessandri of the PN (34.9%) and Radomiro Tomic of the DC (27.8%). In any case, for the Chilean political regime, not obtaining more than half of the votes, it was the parliament, with a majority of the right, that had to ratify the triumph. In spite of pressure from sectors of the bourgeoisie and imperialism, in a climate marked by mobilizations and attacks, the congress finally ratified Allende as elected president. The danger of unleashing a process of rebellion of unpredictable consequences and Allende’s commitment to respect the frameworks of bourgeois legality were decisive in the definition. On November 3, Allende assumed the presidency in the midst of a big popular mobilization.

The Chilean way to socialism

The program of the UP pointed out that “the only truly popular alternative, and therefore the fundamental task facing the People’s Government, is to end the domination of the imperialists, the monopolies, the landowning oligarchy and to begin the construction of socialism in Chile” (I)

When defining how this process would be carried out, Allende said “we are looked upon with fraternal and combative affection by millions of men, women and young people in the world, who see in our experience the conscious attempt of a people who open a powerful channel of transformation through the path of election. Within bourgeois democracy we are going to find the springs that will permit us to carry out the fundamental changes that will profoundly modify the political, economic and social life of our people. We have won through legal channels. We have won through the path established by the play of the laws of bourgeois democracy, and within these channels we are going to make the great and profound transformations that Chile demands and needs. Within the Constitution itself we will modify that Constitution, to give way to the People’s Constitution, which authentically expresses the presence of the people in the conquest and exercise of power. (II) And in his first speech to parliament he said, “Skeptics and doom-makers will say it is not possible. They will say that a Parliament that served the ruling classes so well is incapable of transfiguring itself to become the Parliament of the Chilean People. Furthermore, they have emphatically said that the Armed Forces and the Carabineros, until now the supporters of the institutional order that we will overcome, would not accept to guarantee the popular will determined to build socialism in our country. They forget the patriotic conscience of our Armed Forces and Carabineros, their professional tradition and their submission to civilian power […] For my part, I declare, members of the National Congress, that since this institution is based on the popular vote, nothing in its very nature prevents it from renewing itself to become in fact the Parliament of the people. And I affirm that the Chilean Armed Forces and the Carabineros, keeping faithful to their duty and their tradition of not interfering in the political process, will be the support of a social order that corresponds to the popular will expressed in the terms established by the Constitution”(III)

That is to say, the policy of Popular Unity consisted in reaching socialism through the mechanisms of bourgeois democracy. The reformism of social democracy, assumed by Stalinism, was being put to the test. The result would take on a tragic character soon after.

Once in government, Allende promoted measures to carry out the program of the UP. Copper, the main export product, was nationalized, as was large scale mining of iron, coal, saltpetre and cement. The banking system was nationalized, with 90% of the credit remaining in the hands of the nationalized banks. Nearly 100 factories were nationalized and the social area was given a boost to agrarian reform by expropriating some 1,400 large estates. The resources obtained from these measures served to increase the purchasing power of the popular sectors and to promote housing plans among other social measures. All these measures were voted on in parliament, that is, they were supported by the opposition, especially from the DC, which reflected sectors of the bourgeoisie that did not see any harm in recovering some of the rent given up in view of the imperialist penetration of the last few decades. Of course, the aim of those sectors was that the income recovered should be distributed mainly among the bourgeoisie and not among the popular masses. These class contradictions would explode in a short time.

The right wing reacts, the working class responds

The pressure from Yankee imperialism began quickly, limiting purchases from the country and causing the international price of copper to fall. This aggravated the problems of supply coming from the previous government and caused the appearance of an inflationary spiral. It was the order of the day to advance in the state control of distribution, but Allende’s policy was to tolerate the price increases in the non-nationalized industries, while at the same time authorizing some salary increases to compensate. In this way he sought, consistent with his orientation, to win over or neutralize sectors of the industrial and commercial bourgeoisie, which he would not achieve. In mid-1972 the first demonstrations of the right wing began with cacerolazos. Instead of deepening the path of nationalizations and expropriations, the government backed away from the planned ones and renounced the project of creating a state distribution network. This did not calm the right wing, which in October launched a bosses’ strike led by truck owners and businesses that lasted three weeks.

The response of the working class was not long in coming, mobilizing to break the bosses’ lockout. Defense committees and factory committees were organized and took over production. Industrial cordons emerged, which brought together all the factories in a given sector, with their leaderships elected by the rank and file. They did not have as their axis the economic tasks but rather political ones, such as organizing the defense of the territory, establishing which industries in the sector should move into the social area, and determining the methods of struggle (seizures, mobilizations, concentrations, strikes, etc.). They became a true outline of dual power when they coordinated with neighborhood committees. Instead of playing at mobilizing and developing and centralizing these bodies, the government leaned on the army, giving it all the tasks of control and vigilance and incorporating three military ministers into the cabinet.

Within this framework of polarization, on March 4, 1973, elections were held in which the UP not only won again, but also increased its number of votes, going up to 44%. The Chilean masses were showing that in spite of the difficulties and the fact that criticism of the government’s vacillations was growing in more and more widespread sectors, they were ready to defend their conquests, their organizations and to defeat the reactionary right.

However, the government continued with its orientation, prioritizing dialogue with Christian Democracy. The Communist Party, through its main leader, left no room for doubt “…But together with the opinion of [Christian Democratic leader] Leighton, another one is already taking shape among the non- right-wing tendencies of the PDC [Christian Democratic Party], and she maintains that, just as after the presidential elections, there are favorable objective conditions for seeking the integration of Christian Democracy into government responsibilities. The presence of the Armed Forces in Salvador Allende’s Cabinet is a good help in achieving this possibility, providing a national base that can serve as a bridge for broader political collaboration. If this were possible, it would open up “historical” perspectives since, according to the criteria of those who hold this position, it would be possible to integrate into the base of support of the Popular Unity parties practically the entire base of Christian Democracy, which would achieve a “broad majority” to support the process of political collaboration. And guarantee their essential corrections…” (IV)

From the Tanquetazo to the coup

The government’s hesitations not only disarmed the workers and peasants but also left their hands free for the right wing to continue trying to destabilize the government. Attempts to do this through the regime’s channel by appealing for impeachment or similar variants fizzled out after the March elections and quickly gave way to an attempt to do it through a coup.

On June 29, the 2nd Armored Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Roberto Souper directed his tanks to the Casa de la Moneda, the seat of government, firing several shots while trying to get other regiments to join in. The military rebellion was quelled by the troops commanded by General Prats, head of the army and government minister.

Years later, Pinochet, who had acted under the orders of Prats, recognized that “the action had served so that the intelligence services of the Armed Forces could measure the capacity of response of the pro-People’s Unity forces, register the type of weapons they used and check the level of response of the population to the calls of Salvador Allende. Allende himself in a speech given after the defeat of the tancazo said “And from there I called the people twice by radio. First, to tell them to have confidence in the Armed Forces, the Carabineros and the Investigations […] While these events were taking place – I repeat – the Commander in Chief of the Army, together with Generals Pinochet, Pickering, Urbina and Sepulveda, drew up the plan to repress the subversives. (VI)

While the right wing armed itself for the coup, Allende called for trust in the military like Pinochet and Urbina, who would lead it, or Pickering and Sepulveda Squella who, like Prats, resigned, leaving the way open for the coup. After the Tancazo, a National Security cabinet was created in which the three Commanders in Chief of the Armed Forces and the Director General of the Carabineros Corps joined, according to the CP, to “ensure constitutionality, to tell the whole country that the time has come to normalize the seditious situation. (VII) To complete the conciliatory orientation, the Communist Party dedicated itself to trying to get Christian Democracy to also join the government. This is what its General Secretary said: “We have not pointed out two obligations (of the communists after the elections) but three; the third is to assure that the elections of 1976 are reached and to assure the triumph of a new popular and revolutionary government that will continue the work that it has fallen to comrade Allende to initiate”. These three obligations are intimately linked and at the bottom they outline a revolutionary perspective that only reaffirms the well-known orientation of the Communist Party in the sense of considering that it is possible, in the concrete conditions of our country, to carry out the anti-imperialist and anti-oligarchic revolution and to build socialism without the need for armed confrontation. (VIII) In the midst of polarization the strategy of the CP was to win the elections to be held three years later and to reaffirm the peaceful road to socialism.

Meanwhile, polarization was reflected within the armed forces. In August, the marines of Valparaíso and Talcahuano organized to denounce the preparation of a new coup. Neither the government, nor the PS, nor the CP gave them support, on the contrary they abandoned them to their fate and were imprisoned and tortured by their bosses. Instead of taking advantage of the division of the Armed Forces to win over the bases against the superiors who were responding to the reaction, they continued to trust the commanders, paving the way for the coup.

At the same time, the workers’ movement had begun to arm itself by its own means. In the factories, weapons, Molotov cocktails, grenades, etc. were being manufactured. And the parties also distributed some mainly short arms, as well as some rifles.

Finally, on September 11 the “democratic” General Pinochet led a new coup. At 10:30 in the morning, Allende spoke for the second time and told the workers that he had received an ultimatum to resign. He reaffirmed that he would not resign and regretted that the military had betrayed his professionalism, saying that history would judge them. But he never called on the labor movement to resist. He only said that workers should be vigilant in defending their conquests. Then he said goodbye. Neither the PS nor the CP gave any instructions to their militants or the workers. The instruction of the parties was that the orders of the CUT should be obeyed. And the order of the CUT was to take all the factories, all the workplaces, all the farms, and to remain “alert waiting for new instructions”, but the new instructions never arrived. There was no plan of resistance, no centralized command. The only instruction they had was to stay in their factories: and the military went factory by factory, easily destroying the resistance that was there. The resistance took place, spontaneously and in isolation, factory by factory, in the Industrial Cordons. After Allende’s death, when the left-wing radios were silenced, the military surrounded the factories. The workers resisted from within, but then the bombing of those factories began. The heroic, desperate and isolated resistance of the workers’ vanguard did not succeed in stopping the coup.

September Lessons

The historical account of the events aims to draw the conclusions from a process that was announced as the peaceful road to socialism, with tremendous support and strength from the working class and the peasantry, which ended in a tragedy that meant several thousand deaths, the destruction of the workers’ and popular organizations, the loss of the conquests obtained, and a 17-year dictatorship that changed the economic structure of the country in favor of the big capitalists and imperialism. Trotsky, analyzing the October Revolution, pointed out that without the existence of a revolutionary leadership like the Bolshevik Party, the energy of the masses would have dissipated in bursts without achieving the triumph of the revolution. In Chile, such a leadership did not exist. The Socialist Party and the Communist Party carried to the end their reformist conception, of keeping within the limits of the bourgeois democratic regime. The MIR, a Guevarist force that was not part of the UP, was not up to the task either. One of its leaders wrote in its press: “The Armed Forces have a truly patriotic and democratic role to play together with the people, supporting the workers in their struggle against the exploitation of the bourgeoisie…“(IX) Nor did it have a policy to develop the Industrial Cordons, but rather ignored them by trying to create other artificial bodies outside those that the workers’ movement genuinely had. At most, just as the CP proposed to integrate them into the bureaucratic CUT led by the communists. Unfortunately, Trotskyism lacked a significant presence. There was a radicalization of important sectors in the base of almost all the currents, above all in the Socialist Party, where the criticisms of the reformism of its leadership were very important. But this was not enough to give shape to an alternative leadership that could guide the workers’ and popular forces towards the development of the dual power bodies, the centralization of the defense committees and having a policy towards the rank and file of the army to try to break it. At the time of the final blow of the reaction, there was no organized resistance capable of defeating it and giving the class struggle a perspective to advance towards the socialist revolution.

In the 19th century Marx had already pointed out that ‘the working class cannot simply take possession of the existing state machine and set it in motion for its own ends’ (X) and that it is not an issue regarding ‘passing the bureaucratic-military machine from one hand to another, as has been done up to now, but breaking it, and this is precisely the precondition for any real popular revolution’ (XI), different from those of the bourgeoisie, he developed it in the heat of the experience of the Paris Commune, which he basically defined as “the suppression of the permanent army to replace it with the armed people” and an organism of workers’ democracy that is not parliamentary, but working, legislative and executive at the same time with members elected by the rank and file, who can be revoked and without material privileges. On the basis of these preparations and their own experience, the Bolsheviks promoted the soviets as the form of the new workers’ state. In Chile, where the Industrial Cordons were beginning to be embryos of democratic bodies of dual power and the working class was beginning to arm itself, all these conclusions were overlooked, maintaining the bourgeois State machine, especially its professional army, with known tragic consequences. Unfortunately, sectors claiming to be on the left, progressive or anti-capitalist, do not yet seem to have assimilated the lessons of history. The Chilean Socialist Party definitely went over to the side of the bourgeoisie as guarantor of the post-Pinochet agreement, administering the Capitalist State in the service of the same bourgeoisie that enriched itself during the dictatorship. And at a time when the Chilean people are taking up the struggle again in a real revolution against the remnants of the regime inherited from the dictatorship, the Communist Party and the recently created Frente Amplio are trying to channel all the mobilization through the channels of bourgeois institutions.

For the working class and the popular sectors, the need to create their own bodies of democratic self-determination as instruments of struggle and as the seed of a new state is a fundamental task. The construction of a revolutionary leadership continues to be the greatest challenge so that the energy of the masses does not end up in new frustrations. The Chilean experience, as well as the failed experiences of Latin American progressives in the 21st century, show that it is not by avoiding the radicalization of the masses and making concessions to the right wing that it is possible to neutralize or defeat it and obtain significant gains for the working people, but by developing the democratic organizations of the masses in struggle and a revolutionary leadership that will destroy the economic and institutional bases of the capitalists by advancing the socialist revolution.

- Program of Popular Unity

- Speech at the XXIII Ordinary General Congress of the Socialist Party of Chile, La Serena, January 28, 1971.

- Speech before the Congress of the Republic, May 21, 1971

- Chile Today, No. 43

- “The Road Traveled: Memories of a Soldier, 1990

- Speech by Salvador Allende speaking to the people from La Moneda on June 29, 1973

- Víctor Días, Deputy Secretary General of the CP in El Siglo, August 13, 1973

- Chile Today, No. 40

- Punto Final Magazine (organ of the MIR)

- Marx, The Civil War in France

- Marx, letter to Kugelmann, April 12, 1871