We publish here the report given by our comrade Alejandro Bodart on the October 30, edition of International Panorama.

This week marks the 75th anniversary of the rise of Peronism in Argentina and the tenth anniversary of the death of the leader and ex-president Néstor Kirchiner.

This has opened great debates about history and the present of this political ideology, and we want to stop by and give our position.

Peronism was not the only nationalist movement that emerged in the years of the second postwar. It can be compared to the governments of Cárdenas in Mexico, Vargas in Brazil or Nasser in Egypt.

But what sets Peronism apart is how long it has lasted in time.

Its movement and the Justicialist Party itself that Perón founded still constitute, although weakened, a fundamental leg of the Argentine political regime and in fact still rule nowadays with Alberto Fernandez and Cristina Kirchner.

That is why the history and the journey of Peronism are an essential element to analyze the current political and social situation of Argentina.

The feature that might best explain why this political movement has lasted till this day is its attachment to the working class. However, contrary to Peronism’s own narrative, this class was not born Peronist, let alone nationalist.

The Argentine labor movement emerged during the last decades of the 19th Century, with the development of railroads and the meat industry, while the country became an important agricultural exporter, and with the arrival of millions of European immigrants.

The first unions and federations, the UGT and the FORA, were socialist and anarchist. Some of the first union leaders have been militants of the Paris Commune. Argentina was one of the few non-European countries represented in the First International. In the first May Day rally held in Buenos Aires, there were speeches in four languages.

Even the CGT was founded in 1930 by revolutionary socialists, communists and unionists, and led for the most part by the Communist Party since 1935.

But the disastrous policies and betrayals of these leaders, particularly from the CP, generated great defeats of the labor movement and crushed them as leaders, clearing the way for the Peronist bureaucracy that would displace them.

The steelworkers’ strike of 1942 and the great meat strike following year sealed the fate of the CP at the front of the Argentine labor movement.

In both cases, strong strikes, with all the conditions to win and strengthen the workers, were cancelled by the leadership, condemned by the rank-and-file, in the name of not harming the supply of allies in World War Two.

Stalinism had adopted the policy of the popular front in 1935, imposing the communist parties of the world to form political fronts with the supposedly democratic and progressive bourgeoisies.

Since the Nazi invasion to the USSR, this directly implied an absolute and unconditional support to Yankee and British imperialism.

Argentina was a British semi-colony and most of its production was exported to the United Kingdom. Thus, the salaries and rights of Argentine workers had to be sacrificed in favor of the need to sustain supplies to imperialist Allied troops.

The scandalous betrayal of the meat strike coincided with the arrival of Perón to the Ministry of Labor.

The coronel was part of a Group of United Officials that had taken power on June 4, 1943, to avoid the arrival to the government of a pro-Yankee sector of the bourgeoisie. The army officials of the GOU represented, in turn, the bourgeoisie associated to British imperialism.

The world war imposed Argentina the need to produce goods that were previously imported, and that industrial development generated a great migration from the farms to the cities, creating a new and massive working class.

Perón saw the potential of that new social force and, benefiting from the weakness of the communists and socialists implemented from the Ministry of Labor a policy to organize and co-opt the working class.

On the one hand, it used the favorable economic situation to grant import concessions, like thirteenth salary and paid vacations.

On the other hand, he used that prestige to co-opt the labor organizations. While he massively expanded the unionizing of new sectors, displaced the communist and socialist leaderships, replacing them with bureaucrats controlled from the State apparatus.

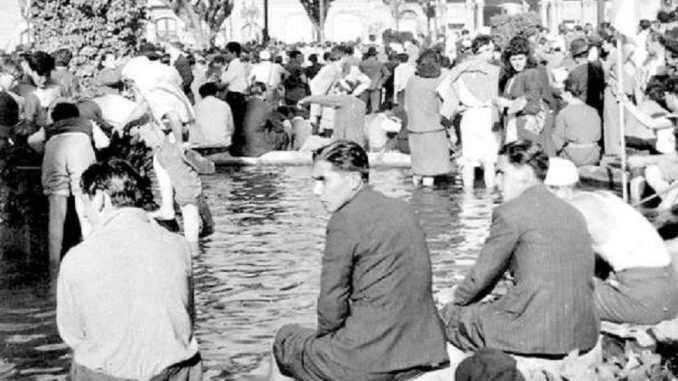

The pressure from the pro-Yankee wing of the bourgeoisie led the government to remove and imprison Perón in 1945. The coronel surrendered and the CGT called for a general strike for the 18 of October. But the mass movement did not wait and took to the streets on the 17 to defend their conquests.

Thousands crowded Plaza de Mayo for long hours forcing the government to release Perón to stop the people’s uprising. The crisis forced the government to call for elections for 4 months later.

Perón ran as a candidate for president on the ballot of the Labor Party of Cipriano Reyes and focused the strength of the unions on the electoral campaign.

His opponents were the pro-Yankee sector with the Democratic Union, which the Radical Civic Union was a part of, as well as the Socialist Party and the Communist Party.

The latter parties, aligned with the United States by Stalin’s orders, faced Peronism accusing it of being fascist and pro-Nazi.

US ambassador Braden´s clear and public leadership of this coalition, led the Peronist campaign to install the slogan Braden or Perón, with signs and graffiti throughout the country.

The 1946 elections were a sweeping victory for Perón and he installed a Bonapartist regime, strongly supported by the working class at the service of the bourgeoisie.

In those years, Perón nationalized the Central Bank, railroads, and public services, created a commercial fleet and monopolized foreign trade at the hands of the State, achieving a relative level of independence from Yankee imperialism, which was already dominant during the postwar.

But all of this was at the service of negotiating in better terms with it and enriching a sector of the bourgeoisie and the British imperialism.

On par with it, he used the extraordinary income granted by the postwar economy to improve the material conditions of his working social base.

The distribution of the national income was the most favorable to employees in history, surpassing 50% in favor of workers. The famous “fifty-fifty” Perón talked about.

But these improvements came with the loss of political independence of the working class.

The CGT and the unions were nationalized, and the Labor Party that Perón had used to run for elections was dissolved and replaced with the Peronist Party, predecessor of the current Justicialist Party.

The labor leader Cipriano Reyes tried to resist and ended up imprisoned, tortured and mutilated.

For the first time, the Argentine labor movement was organized under a bourgeois leadership.

This one promised in its flags “political sovereignty, economic independence and social justice.”

But like any bourgeois leadership, when the surplus of the economic situation started to get shrink, it prioritized capitalist profits.

When the economic crisis began to squander the reserves of the Central Bank, Perón started to restrict his concessions to the workers to maintain the income rates of the local bourgeoisie and give in to the imperialist pressure.

By 1954 the fall in the salary increases was evident, and the economy began to open to Yankee capital with the signing of oil contracts with La California.

Meanwhile imperialism, seeing the government´s deterioration and the opportunity to prop up someone to respond directly to them, prepared together with the Church and the opposing bourgeoisie the gorilla coup of the so called Libertadora in 1955.

The Communist Party and the Socialist Party, continuing their criminal policy in favor of Yankee imperialism, supported that sepoy coup.

The working class took to the streets to face the coup, demanding weapons from Perón. And it had all the necessary strength to defeat it.

But Perón was more afraid of unleashing a mass uprising that could get out of control than of the bourgeoisie that organized the coup. He called the workers to “wait for the storm to pass” and went into exile.

He counted on others to do the dirty work of implementing the austerity measures that capitalism required at that moment and preserve his image as a replacement later. But the wait would be longer than expected.

The unions were outlawed and the Peronist bureaucracy meekly moved to the side, leaving workers to their own devices. But the working class heroically resisted against the dictatorship of the Libertadora.

The current from which the Argentine MST comes, which had initially been built in the labor movement of that time, was an active part of that struggle, doing entrysm in the labor organizations of the Peronist resistance.

Our comrades were founders of the 62 Organizations and Nahuel Moreno led its newspaper Palabra Obrera.

Even though it didn’t last long, until the bureaucracy managed to regain control over the organizations of the Peronist Unionism, that intervention allowed us to build a current with influence in the Argentine labor movement and to organize part of its vanguard in our party, maintaining our political and organizational independence.

The radicalization that spread in Latin America after the Cuban Revolution, the working-class rebellions like the Cordobazo, the Rosariazo or the Tucumanazo, the rise of the union classism current that began to challenge Peronism in the 60’s and 70’s divided the Peronist movement.

On the one hand, we saw the crystallization of the Peronist right linked to sectors of the bourgeoisie and the union bureaucracy.

On the other hand, we saw the rise of the Peronist left, rooted in the students and sectors of the working class, influenced by the guerrilla movements and expressed in organizations like the Montoneros and Peronist Youth that fought for what they called a Socialist Motherland.

These wings faced each other, many times with guns, but when Perón returned in 1973, he didn’t leave any doubts about what his political orientation would be.

The workers uprising had weakened the regime to the point that they had no choice but to turn to Perón as the only figure that could discipline the mass movement.

The center of that policy of the new government of Perón, with his wife Isabelita as vice-president and the pseudo-fascist López Rega as the central figure, was to impose a Social Pact to stop the workers’ struggles.

He kicked the Peronist left out of Plaza de Mayo, calling them “beardless”, and organized the Triple A: the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance. A fascist paramilitary squad that attacked labor and popular organizations of the left, including the Peronist one.

But Perón didn’t finish his task. He died less than a year after taking office.

Isabelita didn’t have the strength or the political authority to play the role that the bourgeoisie and imperialism required of the government. So she was removed by the dictatorship of the Military Junta that would carry out a genocide in the country, killing 30.000 people to crush the vanguard of the working class.

Our current, together with thousands of honest militants of the Peronist left, resisted the dictatorship, but the majority of the political leaderships of the Justicialist Party and the union bureaucracy moved to the side, or worst, collaborated with the dictatorship, even handing over lists of the militants to have them disappeared.

The dictatorship would end in 1983, and Peronism would return to the government in 1989 with Carlos Menem. He won the elections with a campaign that promised “salary surge” and “productive revolution”, but he took office and implemented a blatant neoliberal policy.

He privatized railroads, public services, the national airline, oil and everything he could hand over; he relaxed the labor regulations and international trade; and established what he called “carnal relations” with Yankee imperialism.

The role of the Peronist leaderships in the dictatorship and Menem´s neoliberal and sepoy disaster weakened much of the organic relation that Peronism had maintained with the mass movement for decades.

And the Argentinazo of 2001 was another blow.

The Argentine two-party system would not recover from that popular revolt that overthrew the radical president De la Rúa and four more presidents in two weeks.

Both the Radical and the Justicialist Party were left fractured and discredited.

The revolutionary left advanced during that period, but we didn’t manage to become an alternative for the masses.

Kirchnerism, which had emerged from the ranks of Peronism, appeared as a bourgeois project to stop the turn to the left that had been produced.

To reach power in 2003 and stabilize itself, it had to set itself apart from the Justicialist Party and build a front of various political sectors, adopting some of the demands of the mass movement, and giving come concessions.

Though it gave many illusions, used a center-left double speech and criticized imperialism, Kirchnerism maintained and deepened Argentina´s dependent and extractivist economic model.

Due to the high prices of the commodities, they had an excellent economic situation to implement in-depth changes, improve the situation of the working class and industrialize the country.

Instead, they paid more foreign debt than any other previous government, expanded mega-mining and monoculture of GMOs for exportation.

Even in the field of human rights, they left a lot to be desired.

Due to the pressure of the social struggle after the Argentinazo, the trials against the dictatorship´s repressors resumed, but repression when capitalists required it continued and the government tried to advance the reconstruction of the armed forces, even placing a repressor like Milani as the head.

During their administrations, conquests like same-sex marriage and gender identity were achieved, but these were also won by the struggles, not the Kirchner administration, which in their 12 years, obstructed the legal, safe and free abortion law.

When the prices of commodities fell, Kirchnerism, of course, started to implement austerity measures on the workers and the people. This opened the door for the administration of Macri and the Pro, which deepened the austerity during four years.

Four years in which Kirchnerism and the Peronist union bureaucracy spoke a lot against Macri, but played to save him when the mobilization could have ended him, like it happened in late 2017, when thousands of us mobilized to face the Provisional Reform and managed to stop the Labor Reform.

Now a reunified Peronism has returned to the government, with a front of various sectors that until recently were at each other´s throat, accusing each other of corruption or betrayal, with Kirchnerism in the passenger seat and Alberto Fernández behind the wheel.

They supposedly came to revert Macri´s policies of austerity and submission. Since they arrived, they have prioritized the foreign debt and managed the pandemic without touching the interests of the corporations while the popular economy is crumbling, with 41% of the population and 63% of children under the line of poverty.

These days, there is little left in Alberto and the PJ of Peronism´s mysticism, but the trajectory of the historical movement serves to reaffirm that the solution to the great issues of the Argentine people will never come from that political force.

The urgent task to find these solutions is related to recovering the political independence of the working class in Argentina.

And that is only possible with the left, with an anti-capitalist and socialist program and a revolutionary orientation.

That is the alternative we are building from the MST in the FIT Unidad in our country.