Por Marcela Gottschald

Recientemente, se difundieron imágenes de la que ha sido considerada la mayor crisis que ha afectado a un grupo indígena, los Yanomamis, desde la redemocratización de Brasil. En ellos podemos ver personas, principalmente niños, en un escenario que durante mucho tiempo pensamos que ya no existía en Brasil, la desnutrición extrema.

Unido a esto, el número de muertes también es aterrador, ya que durante el gobierno de Bolsonaro, alrededor de 570 niños Yanomami perdieron la vida por problemas que, con el apoyo adecuado, son fácilmente tratables, como la desnutrición, malaria e infecciones respiratorias.

Pero la crisis Yanomami no es algo nuevo, aunque es visible su agravamiento durante los 4 años de gobierno de Bolsonaro. Esta crisis es un verdadero proyecto militar, y se remonta a la dictadura que asoló el país en las décadas de 1960, 1970 y 1980, lo que demuestra que hubo un esfuerzo consciente para que la situación llegara a tal punto.

No fue una omisión. No fue el olvido. La crisis Yanomami fue un proyecto. Algo desarrollado para eliminar a los que viven y proteger la selva amazónica de la furia destructiva del capitalismo.

Los Yanomamis y su territorio

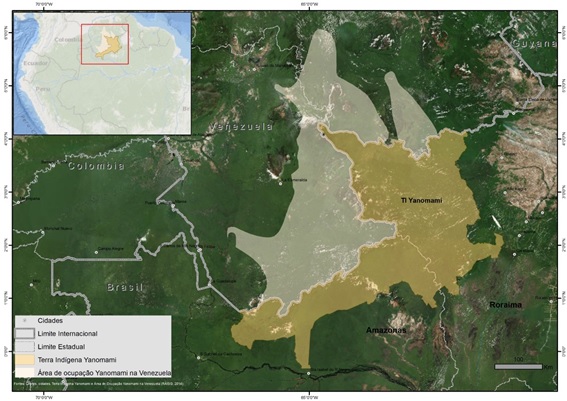

Los Yanomami son un pueblo con poco contacto con la llamada civilización occidental, con algunos grupos que aún viven en total aislamiento. Viven en el norte de la Amazonía brasileña, en los estados de Amazonas y Roraima, y su territorio comprende ambos lados de la frontera con Venezuela.

Su contacto con personas no indígenas, antes esporádico, se intensificó durante la dictadura militar de 1964, donde prevaleció el lema “indio integrado es el que se convierte en trabajo”, y desde entonces ha habido varios períodos de crisis. Siempre teniendo dos agentes en común: los militares y los mineros ilegales.

En el subsuelo de las tierras Yanomami se encuentran numerosos metales, entre ellos el oro. Este hecho, al ser descubierto, atrajo a mineros de distintas localidades, en una nueva “fiebre del oro”, y puso en la mira a todos los indígenas que pudieran interponerse en el camino de este metal.

Sin embargo, con la demarcación de la TI Yanomami, todavía en la década de 1990, y con operativos sistemáticos para sacar a los mineros de la zona, la situación se alivió, al menos momentáneamente.

Pero este momento de relativa calma duró muy poco, y volvió a aumentar el número de mineros ilegales en la región y se produjeron nuevas invasiones. Se estima que durante los últimos cuatro años el número de mineros en tierras Yanomami superó los 20.000, cifra cercana al total de indígenas de esta etnia.

La minería ilegal y el papel del gobierno y de los militares

Al ser un territorio demarcado y una zona forestal importante para el clima planetario, las empresas mineras «legales» no pueden destruir el lugar en busca de oro. Queda la tarea de deforestar, destruir, contaminar y asesinar a los mineros ilegales.

Y para eludir la legislación y hacer posible la minería ilegal, el ejército, como brazo armado del gobierno que debe proteger el territorio, actuó en varios momentos a favor de la minería. Aliado a esto, durante el gobierno de Bolsonaro, los ministros de Estado actuaron en un intento de ayudar en el proceso de extracción de oro, ya sea en forma de concesiones legales o de pasividad en la inspección.

Otro actor importante en este proceso fue el exvicepresidente y general Hamilton Mourão, que durante tres años fue presidente del Consejo Nacional de la Amazonía Legal, órgano cuyo objetivo es “coordinar e integrar los esfuerzos federales para la preservación, protección y desarrollo de la Amazonía brasileña”. Sin embargo, Mourão nombró a militares de su confianza para que asumieran posiciones estratégicas, y juntos trabajaron para intensificar y legalizar la minería en tierras indígenas, contribuyendo enormemente a la calamitosa situación que enfrentamos.

Al mismo tiempo, numerosos cargos de organismos públicos que históricamente protegen la selva y los pueblos indígenas, el Instituto Brasileño del Medio Ambiente (Ibama) y la Fundación Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas (Funai), fueron ocupados por militares. De esta manera, toda la red estatal de protección de los pueblos indígenas y de la Amazonía estuvo, total o parcialmente, bajo el mando de militares.

Y también hay que recordar que la minería, además de destruir la selva y contaminar los ríos por el derrame de mercurio en el agua, impone otros terrores a la población indígena: alejan la caza, llevan alcohol y otras drogas a los jóvenes, reclutan hombres para sus proyectos y violan a mujeres y niñas.

El recrudecimiento de la crisis

Además de los impactos directos e indirectos de la minería, en 2020 se inició el período de la pandemia del COVID-19, enfermedad que afectó de manera desproporcionada a los grupos minoritarios, en especial a los pueblos indígenas.

Por ser más vulnerables a enfermedades infecciosas, como el COVID, los indígenas son considerados un grupo de riesgo, que requiere mayor cuidado tanto en la prevención como en el tratamiento de los casos. Esto es aún más crítico cuando hablamos de indígenas que viven en total o relativo aislamiento, como es el caso de gran parte de la población Yanomami.

Sin embargo, durante la pandemia hubo negligencia intencional por parte del gobierno, que llegó a negar el suministro de agua potable y camas de UCI a la población indígena. La misma negligencia intencional se pudo ver cuando el gobierno ignoró las decenas de solicitudes de asistencia, ya sea para el manejo de casos de enfermedades infecciosas o por desnutrición.

El resultado de todo esto se puede ver hoy.

¿Lo que se está haciendo?

Con la difusión masiva de la situación de los Yanomami, el presidente Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva viajó a Roraima, junto a la ministra de los Pueblos Indígenas Sônia Guajajara, de la Salud, Nísia Trindade, de los Derechos Humanos y Ciudadanía, Silvio Almeida, entre otros, para evaluar e iniciar un plan de acción.

Indígenas en una situación de salud más precaria fueron trasladados a hospitales para recibir un tratamiento adecuado, se dispuso de canastas básicas de alimentos y se reclutaron profesionales de la salud para atender a esta población.

Unido a ello, se “firmó” el compromiso de actuar de manera incisiva y constante para solucionar las causas del problema, las cuales, sin embargo, son múltiples y complejas de resolver. Algunas de las medidas que, según el actual gobierno, se implementarán son:

• Reapertura de las unidades de apoyo de la Funai y Unidades Básicas de Salud;

• Convocatoria de profesionales para trabajar en la región;

• Restringir el acceso al territorio Yanomami, para reducir el riesgo de transmisión de enfermedades;

• Retiro de mineros ilegales, así como de la maquinaria utilizada en la minería.

No sabemos qué medidas de largo plazo se implementarán realmente, ni el impacto que tendrán las acciones de mitigación en el escenario actual. Lo que sí sabemos es que los empresarios vinculados a la minería ilegal no van a dejar las tierras indígenas sin la intervención del Estado, y que éste no puede agachar la cabeza ante el poder del capital. De lo contrario, se repetirán escenas como las que hemos visto y la Amazonía seguirá siendo devastada, agravando aún más la crisis ecológica en la que nos encontramos.

Ante la ya crónica situación de vulnerabilidad y los constantes ataques que viene sufriendo la población Yanomami, así como otras etnias indígenas, es de suma importancia dar seguimiento a las acciones para asegurar que las medidas propuestas sean adecuadas a la gravedad de la situación y que realmente se implementen, incluyendo aquellas que tienen un impacto económico en las empresas vinculadas a la minería ilegal.

Además, es necesario identificar y sancionar a todos aquellos que se benefician de la extracción de oro de las tierras Yanomami, ya que esta es una práctica ilegal y criminal conocida.