El 8 de octubre de 1967 cae herido en combate y es apresado Ernesto Guevara, “el Che”. Al día siguiente es fusilado, fotografiado y expuesto como trofeo por miembros del ejército boliviano y la CIA, para luego ser enterrado en una fosa común pretendiendo con ese acto hacer desaparecer mucho más que un cuerpo. Nunca lo lograron. El Che ya había ocupado un lugar en millones de jóvenes y trabajadores en todo el mundo, y pasaba a convertirse en mito, en ícono, en estrella guía de la rebeldía y la revolución.

El Che nació en Rosario, Argentina, en 1928 en el seno de una familia de clase media alta, ligada a distintos negocios y emprendimientos, que los llevaron a recorrer diferentes lugares del país hasta recalar en Córdoba debido a los problemas de salud de Ernesto, que fue diagnosticado con asma. Más adelante se instalan en Buenos Aires, donde comienza la carrera de medicina en la UBA. Ya por entonces su espíritu aventurero lo lleva a recorrer el país en una bicimoto y embarcarse en la marina mercante. Luego realiza el célebre viaje por Latinoamérica junto a su amigo Alberto Granado. Allí se empapa de la realidad del continente, de los trabajadores, de la miseria extrema de varios lugares, conoce las condiciones laborales inhumanas de los mineros chilenos, colabora con un leprosario en Perú, entre otras experiencias. Ya de vuelta en Argentina completa su carrera y se recibe de Médico.

Emprende entonces un nuevo viaje con la intención de reencontrarse con Granado que estaba en Caracas. Es el año 1953 y Latinoamérica se encuentra convulsionada por las luchas sociales. El Che pasa un tiempo en Bolivia -que aún se sacude por la revolución del 52- donde conoce a Ricardo Rojo, con quien sigue el viaje por Perú y Ecuador. El golpe de Estado organizado por la CÍA contra Jacobo Arbenz en Guatemala le produce un gran impacto y se suma a la resistencia en ese país. En este tiempo profundiza más sus ideas políticas, conoce más a fondo las teorías socialistas, ve los procesos que se van dando en Latinoamérica y Centroamérica, el poder del imperialismo yanqui y su intervención en los golpes de estado y las políticas de los países. Este derrotero termina en México donde consolida sus vínculos con los exiliados cubanos, y termina integrándose al Movimiento 26 de Julio dirigido por Fidel Castro.

Internacionalista militante

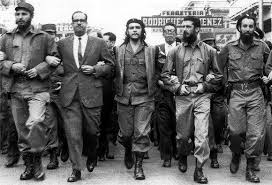

Este movimiento es el que desembarcara en Cuba y que luego de un largo derrotero y varias veces a punto de fracasar, lograría en los primeros días de 1959 derrotar a la dictadura de Batista, acompañado del apoyo popular, obrero y campesino, el desarrollo de huelgas y el crecimiento de dicho movimiento.

Consumada la Revolución Cubana, el Che Guevara ocuparía varios cargos en el gobierno, como Ministro de Industria, Presidente del Banco Central y uno de los encargados de las relaciones exteriores del flamante gobierno. Ya con la Revolución declarada como socialista, el Che viaja a Argel, al Congo y Angola para desarrollar y colaborar con las fuerzas insurrectas de ese país. Se empiezan a hacer visibles las diferencias con Fidel y con el régimen stalinista de la Unión Soviética, a quien denuncia por su rol en la guerra de Vietnam: “El imperialismo norteamericano es culpable de agresión; sus crímenes son inmensos y repartidos por todo el orbe. ¡Ya lo sabemos, señores! Pero también son culpables los que en el momento de definición vacilaron en hacer de Vietnam parte inviolable del territorio socialista, corriendo, así, los riesgos de una guerra de alcance mundial, pero también obligando a una decisión a los imperialistas norteamericanos. Y son culpables los que mantienen una guerra de denuestos y zancadillas comenzada hace ya buen tiempo por los representantes de las dos más grandes potencias del campo socialista.” [1]

En esa misma conferencia diría que “crear dos, tres…muchos Vietnam es la consigna”

Con estas palabras el Che mostraba que su proceso de evolución política no solo lo transformaba en un internacionalista cada día más consecuente, sino que al mismo tiempo lo alejaba del papel nefasto de la Unión Soviética y el acercamiento a la misma que se acentuaba en el gobierno cubano.

Consecuente con esa idea decide iniciar en Bolivia el camino para una nueva insurrección en Latinoamérica, donde encuentra su final.

Algunos debates

Reivindicar al Che, su figura, su trayectoria revolucionaria y su legado no significa hacer culto a la personalidad y aceptar acríticamente todas sus concepciones como si fueran recetas infalibles para todo tiempo y lugar. Para quienes luchamos por terminar con este sistema se trata de rescatar los aciertos sin por eso dejar de cuestionar lo que consideramos concepciones equivocadas, con el objetivo de fortalecer la acción revolucionaria.

A partir de la experiencia cubana Guevara hizo del método de la guerra de guerrillas una teoría: el foco guerrillero. A esta teoría foquista adhirieron muchas organizaciones a lo largo del mundo, fundamentalmente de América Central y Latina. En un momento de ascenso de la resistencia obrera, de disputa y polarización, con gobiernos dictatoriales acechando el continente, no fueron pocas las discusiones y polémicas que surgieron entre las corrientes de izquierda, la vanguardia y el activismo. Nuestra corriente sostuvo entonces un duro debate con el foquismo, cuestionando el hecho de que pretendía trasladar mecánicamente la experiencia guerrillera a las distintas realidades de América, elevando al campesinado como la vanguardia revolucionaria sin tomar en cuenta el análisis particular de cada país, separándose del movimiento obrero, absorbiendo a los mejores activistas para esta política y actuando separados del movimiento de masas, y muchas veces en su nombre pero sin haber consultado o siendo parte de las organizaciones obreras. La historia demostró que esta teoría que elevaba a estrategia la táctica de guerrilla, terminó fracasando en casi todo el continente, provocando la muerte de miles de abnegados y valientes luchadores. El Che tampoco le dio importancia a la construcción de partidos revolucionarios, la otra tarea estratégica junto a la movilización de la clase obrera. La combinación de esos déficit políticos llevó a quienes lo siguieron ciegamente a no poder encontrar nuevos triunfos los años siguientes.

Pese a estos debates, nunca dejamos de reconocer la valía del Che Guevara. En su trabajo titulado “Guevara: héroe y mártir de la revolución permanente” Nahuel Moreno decía “Guevara, que se jugó la vida cuantas veces fue necesario, hasta perderla, por la revolución cubana y latinoamericana, no tuvo temor de enfrentar y dar respuesta a los problemas más graves planteados a la revolución. Desde la defensa de Cuba hasta la construcción del socialismo en la etapa de transición, pasando por las relaciones económicas entre los países socialistas, no hubo problema de importancia decisiva en la lucha de los trabajadores que Guevara no abordara, para darle una salida: la revolución permanente.”[2]

Revolución socialista o caricatura de revolución

Pero si algo se destaca de Che, es su lucha consecuente por una sociedad sin explotación ni violencia, por una sociedad socialista. En el marco de un mundo signado por los acuerdos de Yalta y Postdam, el de la coexistencia pacífica de la burocracia soviética que justificaba el abandono de la lucha por el socialismo en los países semi coloniales con la teoría de la revolución por etapas, el Che fue un rebelde. A quienes por escepticismo o por su identificación con el estalinismo planteaban que América Latina no estaba madura para el socialismo y buscaban acuerdos con las burguesías nacionales progresistas “Por otra parte las burguesías autóctonas han perdido toda su capacidad de oposición al imperialismo y solo forman su furgón de cola. No hay más cambios que hacer; o revolución socialista o caricatura de revolución.” [3] ¡Cuanta vigencia tiene esa frase cuando nuevamente hay quienes desde la izquierda el progresismo insisten con ser furgón de cola de la burguesía nacional! Reivindicar al Che en estos tiempos significa para nosotros colocar la lucha por el socialismo como un horizonte posible, con su fuerza y su convicción.

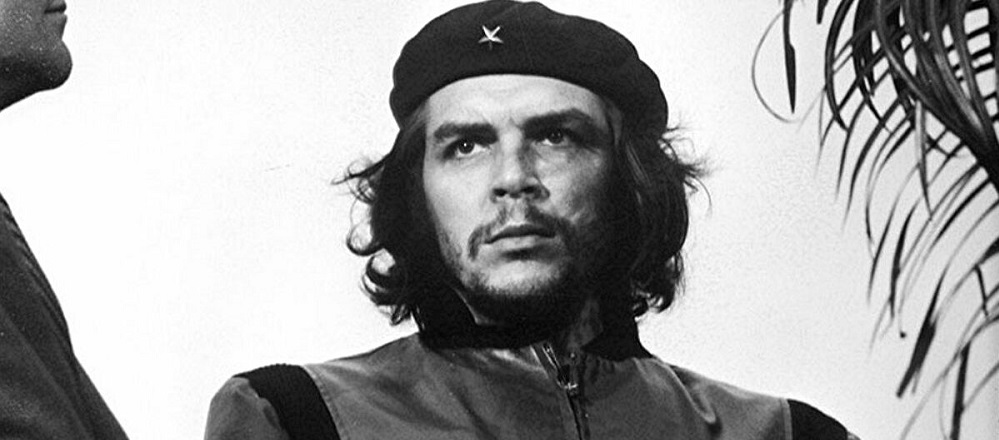

A 53 años de su asesinato queremos recordar a ese revolucionario, que hoy es bandera en todas las luchas a lo largo y ancho del mundo, que se sembró y florece cada vez que un joven sale a dar pelea, cada vez que un laburante decide salir a defender sus derechos, cada vez que su imagen, esa imagen eternizada por Korda, se convierte en una adarga frente a las injusticias. Lo recordamos recuperando las palabras que dedicó a sus hijos cuando partió de Cuba para internacionalizar la revolución y que son una guía: “Crezcan como buenos revolucionarios. Estudien mucho para poder dominar la técnica que permite dominar la naturaleza. Acuérdense que la Revolución es lo importante y que cada uno de nosotros, solo, no vale nada. Sobre todo, sean siempre capaces de sentir en lo más hondo cualquier injusticia cometida contra cualquiera en cualquier parte del mundo. Es la cualidad más linda de un revolucionario.”[4]

Juan Bonatto

Notas

- Mensaje a los pueblos del mundo a través de la Tricontinental, 1967

- Nahuel Moreno. “Guevara: Héroe y Mártir de la Revolución permanente.” 1967

- Mensaje a los pueblos del mundo a través de la Tricontinental, 1967

- Carta del “Che” a sus hijos, 1965