Por: Luis Meiners

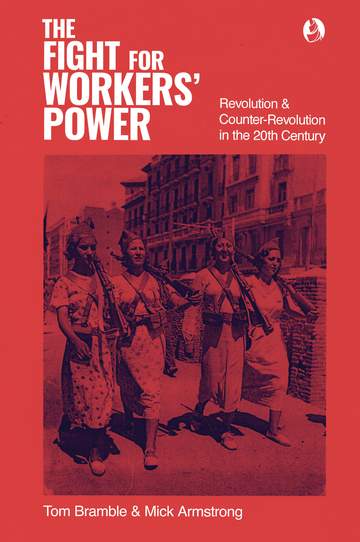

El libro “The Fight for workers´ power: Revolution and counter-revolution in the 20th Century” (La lucha por el poder de los trabajadores: Revolución y contrarrevolución en el siglo XX) de Tom Bramble y Mick Armstrong recorre la lucha de clases en el pasado reciente y brinda importantes lecciones para el presente. Los autores, ambos militantes socialistas de larga trayectoria y miembros fundadores de Socialist Alternative, analizan la historia desde una perspectiva militante sin por ello perder en rigor análitico e histórico.

El alcance de la obra, tanto en términos temporales como geográficos, le agrega un interés particular. Analiza eventos desde 1914 hasta 1956, que acontecen alrededor del mundo, desde las minas de carbón australianas hasta los puertos de la Costa Oeste de EEUU, pasando por China, Rusia, el Este europeo, Grecia, Italia, Francia, España, Alemania e Inglaterra. Esto aporta una enorme cantidad de evidencia histórica que sustenta las principales conclusiones de la obra.

Un elemento central del libro, y una de sus principales contribuciones, es que coloca en el centro del análisis el papel de las direcciones. Para ello pone el foco en situaciones revolucionarias o situaciones de ascenso en las que la lucha de clases se vuelve particularmente aguda, y también en derrotas y contrarrevoluciones que dejaron una marca en el siglo XX. Examina las políticas y orientaciones impulsadas por quienes estaban al frente de las principales organizaciones en cada uno de esos momentos históricos, y el impacto que éstas tuvieron en el devenir de los acontecimientos. En este sentido, destaca la centralidad de la disputa por la dirección de la clase trabajadora.

Comenzando con la traición del reformismo en prólogo a la Primera Guerra Mundial, repasa las polémicas más importantes que dieron forma al movimiento revolucionario de posguerra cuando estallaron revoluciones en gran parte de Europa. Del triunfo de los bolcheviques a la tragedia Alemana y los debates en el seno de la Tercera Internacional, recorre los peligros del oportunismo y el ultraizquierdismo. Señala la importancia de la organización internacional y de la flexibilidad táctica y claridad estratégica expresada en elementos como las “21 condiciones” y la táctica del Frente Único.

Luego examina la contrarrevolución estalinista en la URSS, la degeneración de la internacional y su impacto en los puntos álgidos de la lucha de clases como la huelga general inglesa de 1926 y la revolución China. Con el control cada vez más firme del estalinismo sobre la internacional y los Partidos Comunistas, aborda los giros del “tercer periodo” y el Frente Popular, y sus consecuencias, frecuentemente trágicas, en Alemania, España, Australia, Francia y Estados Unidos. En el caso de España, además, revisa el rol del anarquismo en un proceso en el que esta corriente tuvo un importante peso.

Finalmente cubre el papel del estalinismo desviando el ascenso de la resistencia anti-fascista en Italia y Grecia, el aplastamiento de las revueltas anti-burocráticas en el Este Europeo y el desarrollo de la revolución China y el papel del Maoísmo.

Más allá de los matices o diferencias que uno pueda tener con algunas de las caracterizaciones realizadas por los autores a lo largo de este recorrido histórico, realizan un gran aporte mediante abundante evidencia demostrando la enorme energía revolucionaria de la clase trabajadora y las masas. Esta podría haber cambiado el curso de la historia en más de una ocasión durante el siglo XX. Si no lo hizo no fue por sus propios límites, sino por el rol de las direcciones reformistas y contrarrevolucionarias, y la ausencia de una dirección revolucionaria que estuviera a la altura de los acontecimientos. Tal como señalan los autores:

“Culpar a las masas por los fracasos de las direcciones es una pobre excusa, un medio a través del cual se minimiza el papel de la dirección revolucionaria. Por supuesto, hay periodos históricos enteros en los que aún la dirección revolucionaria más visionaria nada podría haber hecho para hacer avanzar el ritmo de los acontecimientos. Pero hay otros periodos en los que la dirección revolucionaria puede hacer una diferencia decisiva.” (pág. 118)

En este sentido “La lucha por el poder de los trabajadores” nos recuerda enseñanzas fundamentales para quienes seguimos comprometidos en la lucha contra la barbarie capitalista. En especial, la centralidad de la lucha por la dirección de la clase trabajadora y la necesidad de construir un partido revolucionario enraizado en sus luchas, una organización militante construida por cuadros comprometidos, como herramienta indispensable para esta tarea. Por todo ello, es una obra cuya lectura sin dudas será un valioso aporte para la formación de esos cuadros.

Vivimos en un periodo de crisis y rebeliones. Alrededor del mundo hemos visto a los pueblos dar enormes muestras de su energía de lucha. Sin embargo, desde los sectores reformistas y defensores de “lo posible” insisten en responsabilizar a las masas por los límites que sus propias orientaciones políticas les imponen. Las y los revolucionarios tenemos la tarea de disputar contra a estos agoreros del “no se puede”. Este libro nos brinda herramientas para ello.