Today marks a new anniversary of the struggle that the Algerian people led against the French occupation. The Algerian independence war lingered over eight years of massacres, generalized tortures, militants imprisoned by the French army and a long journey of resistance of the Algerian people for their self-determination and national sovereignty that had a deep importance for the rest of Anglo-French colonial territories in Africa.

The Revolutionary Committee for Unity and Action (CRUA), integrated by a high nationalist leadership and the heads of the revolution, founded Algiers in July of 1954—nowadays its most populated capital and city—with the intention of uniting there all the groups and independence tendencies to launch an armed struggle against the occupation. On November 1st of that same year, the National Liberation Front declared war to France.

The occupation

Algeria was invaded by France in 1830, in a time of constant territorial expansion by the central countries in the struggle for the occupation of the world. The policy of the French government was to populate Algeria with French people, and by 1910 there were already 400,000 settlers in the Algerian territory. That is how they created a social base that legitimized the violence of the local power in politics, the economy and the army.

For more than a hundred years, the people lived through the misery of the occupation, a constant war hidden behind that classic façade of peaceful intervention. The stripping of the farmers of their best lands and its subsequent handing over to the settlers, the physical elimination of their traditional leaders, the dismantling of their education system and the imposing of the French language in education are some of the examples.

Until then, a farmer had access to the land by being a member of a tribe or by receiving it in a usufruct. After the conquest by the French State and the appropriation of those lands, the farmers were brutally evicted and in 1863 the right to individual private property was established on the lands that were previously collective. Thus, the poor farmers and the complex balance between the sedentary populations and the tribes of nomad shepherds were destroyed in one blow.

The germ of the anti-colonial struggle

During World War I, many Algerians participated in the Western front fighting for France in terrible conditions, as light infantry that harassed other armies, or in other words, as cannon fodder. The early 1920’s saw the rise of a new movement against the Gaul occupation that counted with the support of Algerian intellectuals. Later the “Etoile Nord-Africaine (North African Star)” was founded. This was an independence faction that counted with the support of the French-Algerian Communist Party.

For the Second War, they were called once again, this time, to free France from the German occupation, once again without their autonomy being recognized. The 1930’s saw the rise of a movement formed by small traders and the farmers in decay from the last movement, who condemned the fate of the budget for religious heterogeneity and proposed the return to the purity of the Coran, the expansion of the reformist Islam, and created numerous reformist schools and organizations of all kinds.

This phenomenon was combined with the migration of Algerian workers to the suburbs of the cities and both built to strengthen nationalism. The emigration of poor farmers and the relocation of the children of the medium farmers for their education in the most concentrated cities served to structure a new network of social relations and promote the organization against France in the midst of the social unrest.

The participation of the North African countries in the anti-fascist war and the German occupation in France in 1940 hit the colonial pact. After the end of the war, that anti-colonial sentiment begins to intensify.

The massacres of Guelma and Sétif

On the 8 of May of 1945, while France was celebrating the defeat of Nazism, thousands of Algerians marched in the streets of Sétif, to the east of the African country, to demand their independence from France’s dominion.

For the celebration, there was a procession of Muslims with Algerian flags and signs that requested the release of Messali Hadj, a leader and militant of the left nationalism and also the founder of the African Northern Star. When the police intervened to remove them, they were rejected. Then a security agent shot killing a young man of 20 years that was waving one of the flags and started a brutal combat enabling the scattering of the demonstrators by shooting.

The hatred of more than 100 years of colonial subjugation, of submission and oppression was avenged by the Algerians with the murdering of 102 Europeans. As a disciplinary measure, the government retaliated with 45,000 Algerians murdered and a system of organized tortures for which France did not took responsibility until 2008.

The independence war

Time worsened the hardships of Algerians. The massacres of 1945 were the last straw. To encourage their fading into oblivion, De Gaulle said in London that “blood soon dries” but he was wrong. It was reborn in a resistance that in the following decade grew increasingly faster and weakened France with each step.

The Algerian people, who had been deprived of their lands and pushed to unproductive areas, was left without their traditional mechanisms of economic security and, without their political family structure, massively migrated to the cities and turned to the armed struggle.

On November 1st, 1954, there were numerous attacks to police stations, ambushes, explosions and fires against the settlers inaugurating the armed struggle through urban and rural guerrillas lead by the National Liberation Front that counted at first with 500 militants but that quickly filled its ranks due to the increasing repression.

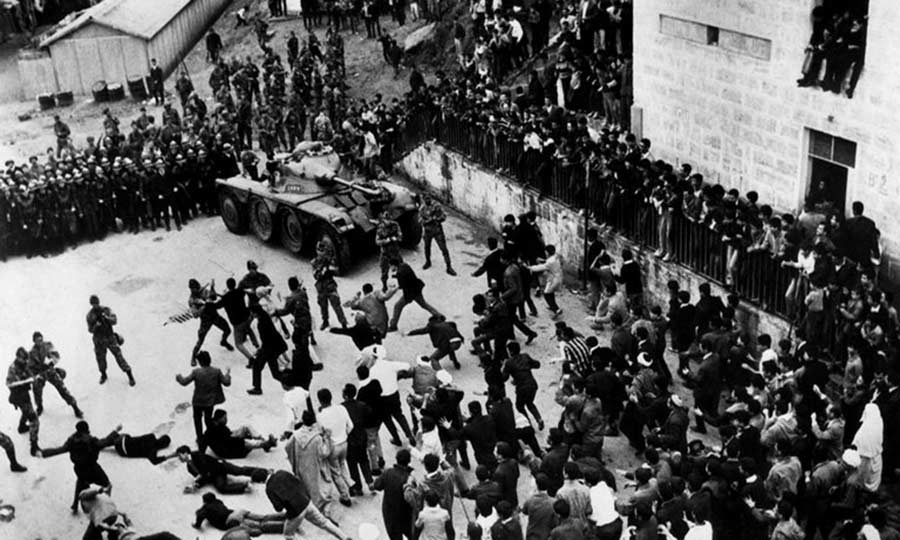

Between 1956 and 1957, during the Battle of Algiers, the FLN attacked French targets and this time was resisted by paratroopers, marking the intensification of the conflict with the settlers. The Gaul general Jaques Massu implemented tortures and the summary execution of thousands of Algerians that advocated the independence cause.

The French settlers made several riots in Algeria, demanding the return to power of the general Charles de Gaulle, who returned to rule the State in the face of the risk a civil war in his country. A new military uprising of the settlers took place in January of 1960, though it failed due to a lack of support.

The National Liberation Front

The organization had a moderate wing lead by Ben Khedda, Mohammed Boudiaf and Hocine Ait Ahmed and a “socialist” wing, led by Ben Bell, Mohammed Khider amd Houari Boumedienne – Chief of Staff of the Army. Not all Algerians were convinced from the get go in the complete rupture with France, but by 1956 the French army had mobilized half a million soldiers.

After the bloody liberation war, on March 18, 1962, the French administration of the Gaulle and the FLN, signed the Evian Accords that established a ceasefire and the call for a referendum of self-determination. Algeria gained independence on July 5, 1968, and, after the first elections in the month of September, Ferhat Abbas was elected President of the National Constituent Assembly. Almost a million Europeans left the country, among them were administrators, businessmen and technicians.

In April of 1963, Ben Bella took over the ruling of the country after a great struggle for power, drafted the Constitution that was then passed in 1963. Later, the properties of the French were nationalized, as well as other companies considered crucial for the economy of the country. Also the self-managing of the small and medium enterprises was decided, an agricultural reform began and a women liberation program was designed. Furthermore, a new literacy program was launched, as well as an Arabization campaign that generated some protests and Berbers revolts.

An aborted revolution

The liberation of Algeria reopens a parenthesis of revolutionary euphoria in all Maghreb, which in turn was inspired and preceded by the French defeats in Dien Ben Phu, Vietnam and Indochina, weakening the country each time. The French CP, just like the rest of the postwar revolutions, had a policy of abandonment of the peoples that fought to free themselves from the stranglehold of the colonies and said that supporting these movements was helping fascism.

The Algerian FLN, due to the limitations and its place in the workers’ and farmers’ movement, retreated and limited itself to rebuilding a bourgeois State, opposite to the progress the revolution had already achieved. It had no intentions of breaking up with the bourgeoisie, but it was the bourgeoisie and its parties had broken up with them in a quick alliance with the French colony fleeing the country.

A popular front was not possible due to the lack of parties and, thus, they had to go beyond their own limits. That is how French imperialism, seeing that the revolution was moving forward, gave them concessions, democratic freedom and ceasefire in the face of the imminent continuation of the revolutionary process because they did not want to lose everything. In its place, they build a semi-colonial bourgeois State, dependent on French and North American imperialism, instead of the previous colonial State. That organization was at the head of the government and crushed several organizations throughout history, like the Arab Spring in 1988 and its re-edition in 2011. The Algerian people are still standing and took to the streets once again with democratic demands in April of last year. Those people are the heir of the liberation of 1954. They are still standing and will fight again to reclaim what is theirs. The government of their own fates.

With collaboration by Anabella Delinger