Automatic translation made by AI

On July 2, in Bagneux, in the Paris region, in response to an invitation from Lucie Castets (an “independent left” personality whom the deputies of the New Popular Front (NFP) had proposed as prime minister), leaders of the Socialist Party (PS), the Ecologists and various smaller organizations that had emerged from the various crises of the PS and Unsubmissive France (LFI)¹ met to discuss. The subject of the discussion was not the preparation to sweep away Macron, Bayrou and their reactionary policies through the class struggle, but to reach an agreement on the burning issue… the 2027 presidential elections!

By Gérard Florenson

Electoral illusions and personal ambitions

All the participants believe that the “left” should unite around a single candidacy in the first round, a candidacy that, given the divisions between the right and the center, would advance to the second round and, thanks to the “republican wave”, defeat the representative of the National Regroupment (RN).

Apart from the assumption that there won’t be a major social or political crisis in the next two years – a question that has yet to be defined, given the recent press conference by Prime Minister François Bayrou and his entire cabinet, essentially announcing an austerity plan that declares war on workers – and therefore that the electoral deadlines will be respected, there is a certain blindness in not foreseeing the likely collusion between an increasingly reactionary right and an extreme right that tries to look respectable². Or, more precisely, the legalistic left believes it can attract voters from the “moderate” right to a candidate who is not too radical.

The pre-selection of the candidate was not on the agenda of the meeting – only the primaries were mentioned without going into detail – but everyone was clearly thinking about it. Those present, at least three of whom are openly aspiring (Lucie Castets, Clémentine Autain and François Ruffin), the PS (Socialist Party), with the possibility of launching one of its own candidates, and also those absent: the French Communist Party (PCF), which remains silent; the LFI, for which Jean-Luc Mélenchon is undisputed; and Raphaël Glucksmann, who believes that the polls will show who is best placed.

The New Popular Front, a knife without a blade

Apart from the ridiculous rivalry between those who already see themselves in the Elysée Palace, the divisions are evident. After the second round of the legislative elections, the leadership of the PS and the Greens seriously considered extending the “republican front”, responding to Macron’s proposal to form a government that would exclude the RN. This quickly proved impractical, as it meant the end of the NFP, since Macron’s project excluded the “extremists”, both the LFI and the RN and their allies.

It also meant abandoning the fight against the dismantling of the pension system, Macron’s flagship reform, supported by the Republicans, whose political influence far outweighs the number of their representatives. The PS would have settled for a “real negotiation”, but the price to pay would have been considerable. Indeed, the creation of the NFP and its relative success had raised hopes (and illusions) among the “people of the left”, as well as simply preventing a possible NR government. Taking responsibility for breaking this alliance was unthinkable.

But what united all the parties that make up the NFP was to limit their response to the attacks of the government and capital to the institutional arena, avoiding taking it to the terrain of the class struggle, to the resumption of strikes and demonstrations, despite the fact that many of their voters went to the polls in search of revenge after the defeat of the pension reform.

To entertain the public, a “great democratic campaign” was launched – with petitions – to demand that Macron appoint a prime minister from the NFP, the main force in parliament and, ironically, in the name of the “traditions of the Fifth Republic”, even threatening to oust the president⁴. Then came the votes of no confidence of variable geometry, whose fate depended on the votes of the NR and whose success would only have served to replace one right-wing government with another, Bayrou instead of Barnier. All this while waiting for the next elections, especially the presidential ones, which would monopolize all their attention.

Doomed to division

Some of the NFP forces want to play the “realism” and respectability card, believing they are in tune with the aspirations of the electorate and possibly preparing future alliances with the “center”. Others, like the LFI, seem more radical, demanding “the entire NFP program”. But while this program has nothing anti-capitalist about it, they all position themselves on the institutional and parliamentary terrain, with some patriotic speeches from Jean-Luc Mélenchon, defender of “our national industries” and even “our armed forces”. And, of course, the presidential elections are the only way out.

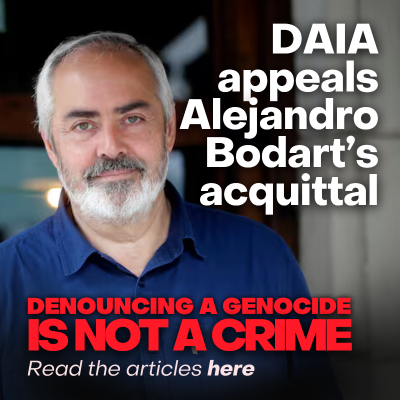

But the fractures are evident on many issues. Thus, the PS shamelessly revives accusations of left-wing Islamism and even anti-Semitism against the LFI, and is careful not to openly condemn the crimes of the Israeli government. This is not surprising, since social democracy has always supported Zionism and the Israeli Labor Party is part of the Socialist International. But legitimizing the genocide against the Palestinians by joining the hate campaign against those who denounce it? In fact, the Socialist Party seeks common ground with Macron’s “balanced” positions, considering Netanyahu’s policy somewhat excessive, while denouncing the “terrorism” of Hamas⁵. But the PS’s disgrace goes beyond the Palestinian question: it supports state-sponsored Islamophobia on all fronts, thus feeding the confusion between migrants and criminality.

Another significant episode: we have just seen Olivier Faure defend the municipal police’s right to bear arms (and use them?) in the face of a modest proposal by the LFI to disarm them. It’s true that “socialist” governments have extended the prerogatives of the police, allowing them to shoot if they refuse to stop. We regularly see the consequences of that blank check given to the police under François Hollande (law of February 28, 2017).

This raises questions about the limits of the LFI’s position, which would otherwise favor the strengthening of the national police. But what is clear is that, faced with every attack from the right, the so-called left retreats, tries to justify itself, appears reasonable and moderate, thus distancing itself from the more radical proposals.

The “Anticapitalist” NPA, following the New Popular Front

It didn’t take long for the leaders of the NPA-A, breaking with their own history, to succumb to the charms of left-wing unity. It would be cruel to remind them, just when their party has just joined the self-proclaimed Fourth International, of this quote from the Transition Program, which they still claim to support:

“The Fourth International already enjoys the deserved hatred of the Stalinists, the Social Democrats, the bourgeois liberals and the fascists. It does not and cannot belong to any of the popular fronts. It is irreducibly opposed to all political groupings linked to the bourgeoisie.”

Excerpt from the resolutions of the NPA-A congress (February 2025):”

POLITICAL UNITY AND OUR TASKS IN THE ELECTIONS

Political unity is a permanent struggle and, in this period marked by the possibility of the extreme right coming to power, it extends to the electoral arena to demonstrate the need for anti-fascist unity at all levels.

In this sense, the experience of the New Popular Front is an achievement. The NFP brought together left-wing parties, unions and associations, attracting tens of thousands of militants, but also many unorganized people or those entering politics for the first time, with radical forces (especially the FI, but also the CGT and the FSU) at its core. The NFP’s victory over the extreme right in the 2024 legislative elections demonstrates that the labour movement’s capacity for resilience and mobilization remains significant.

However, we also face its limits. In particular, the desire of the main left-wing parties (including the LFI) to maintain the NFP as a mere electoral cartel. We, on the other hand, are fighting for the NFP to fully develop as a social and political front that expresses itself both on the streets, in the struggles and in the electoral arena. To do this, we rely on forces that maintain essentially the same politics as us within the NFP (Ensemble, GES, GDS, etc.), as well as on the embryonic national coordination established around the “victory trains” initiative, the Copernicus Foundation and the NFP committees involved.

Here, some differences with the revolutionary Marxist orientation can be observed. The NFP is viewed with some reservations due to its limitation to the electoral arena (and FSU and CGT bureaucrats are labeled “radicals”), but there is no critical assessment of the “republican front” that helped save Macron’s party parliamentary seats and even those of the right. The NPA-A embraces the NFP’s “victory”, confusing the first-round vote with a parliamentary majority; it therefore joined the “democratic campaign” demanding that Macron “respect the will of the voters”, when, as we noted above, the aim was precisely to restrict the rejection of bosses’ and government policies to the electoral arena.

Logically, the leaders of the NPA-A do not seek to converge, either for struggles or elections, with revolutionary organizations (LO, Révolution Permanente, NPA-R) and instead look to the small groups of the so-called radical reformist left.

What else can we say, except that we hope these comrades – at least some of them – will reconsider?

You may also be interested in: France: Public deficit, austerity and rearmament

Notes

1. APRES, formed by those excluded from the LFI, has just held its founding congress. It has joined the Ensemble, a group that includes dissident groups from the LCR and the NPA, some still members of the Fourth International (SU); DEBOUT, the small party of François Ruffin, another former LFI member with his own agenda; GÉNÉRATIONS, the party of Benoît Hamon, former PS candidate in the presidential elections…

2. Philippe Poutou paid a high price in the electoral district of Audoise, ceded by the NFP. In the second round, he won a few votes from the local dissident PS candidate and little else. The results show that the “republican” right voted en masse for the outgoing RN MP.

3. The nature of the NFP, which aims to “civilize” capitalism a little, is one thing; the aspirations of its voters, mostly young and working class, who seek revenge after successive defeats without waiting for the next election, are another.

4. With a single-shift proportional electoral system, NR and its allies would have won the largest number of seats. Was it necessary, in the name of democracy, to demand a Bardella government?

5 – This in no way justifies the LFI’s “campism”, which is always condescending towards the Russian and Chinese governments.