By Farooq Sulehria and Harris Qadeer, Jammu and Kashmir

Originally published on greenleft.org.au

Often, when Kashmir makes the headlines, it is about the Indian-administered state of Jammu and Kashmir (IaJK). However, an anti-neoliberal intifada is taking place on the streets of Pakistani-administered Jammu and Kashmir (PaJK) that deserves global attention.

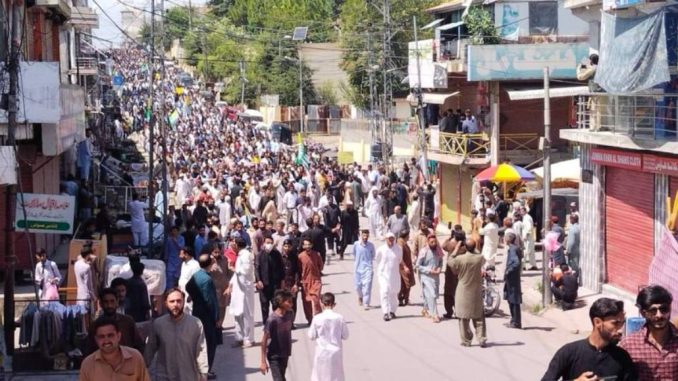

Blacked out even in the Pakistani mainstream media, and in its fifth month, this movement manifested mass power yet again on October 5, when a general strike was observed across PaJK. Markets were closed, there was no traffic and the streets were empty. More importantly: for the second month in a row, the majority of people in major towns refused to pay their monthly electricity bills.

The PaJK left is playing an instrumental role in the mass movement, and the refusal to pay electricity bills on a mass scale — more than 70% did not pay their bills in October — combined with peaceful mass street-agitation is unnerving the PaJK government — which controls PaJK from Pakistan’s capital, Islamabad.

While spiraling electricity prices proved the trigger for ongoing protests, the other key demand is to restore the subsidy on wheat prices. Erosion of the subsidy over time has resulted in the doubling of the price of bread since the COVID-19 pandemic.

It all started in May, with a dharna (sit-in ) in Rawalakot, a scenic town in the Himalayas, known for being the hub of socialist and secular-nationalist impulses. A handful of left and secular-nationalist activists staged the indefinite sit-in, to protest the end of the subsidy on wheat and other edibles, increases in power tariffs and scandalously luxurious perks enjoyed by government officials, including politicians.

Top bureaucrats are often imported from Pakistan, while local politicians are seen as collaborators. PaJK, unlike IaJKl, apparently has “independent” status. Dubbed as a semi-colony by critics, PaJk has a parliament that elects the prime minister and the president, but has no control over defence, foreign policy, or currency. Its independent status is symbolised by its own flag.

A number of other symbolic theatrics differentiate PaJK from the IaJK. Most importantly, the Pakistani state does not prove as brutal as is the case with India. However, this is not due to any humanitarian impulses informing the Pakistani state. Elsewhere — in East Pakistan and Balochistan province — it has proven itself as brutal as India has been in the valley of Kashmir.

Left and secular nationalist forces

The critical factor in the case of PaJk is its left-wing forces, consisting of Marxist groups as well as secular nationalists. The left learnt its lessons from PaJK history and benefits from an ideological maturity.

An armed uprising to wrestle control from Pakistan in the 1950s did not prove very successful. It ended up in the “Baral Accord”, entailing some concessions to the PaJK tribal leadership, which developed a patron-client relationship with Pakistan. Learning a lesson from this experience, mass movements in PaJk have largely stayed peaceful.

Secondly, unlike IaJK, the nationalist opposition to Pakistani domination has stayed staunchly secular. In IaJK, from the 1980s onwards, the leadership gave Islamic colour to their struggle against New Delhi. Pakistan, of course, patronised the Islamified leadership in the Kashmir Valley on the Indian side. New Delhi, at least initially, was also happy to encourage Islamic fundamentalists to counter a secular Kashmiri leadership in this conflict-ridden region.

In summary, secular and socialist forces have maintained a considerable position in PaJk politics. Hence, the sit-in staged first time in May this year — and still in place at the time of writing — has also attracted traders.

The traders and transporters constitute an important sociopolitical segment in the absence of industry. The state is the largest employer. Importantly, in terms of development, PaJk has performed exceptionally well on two counts in the context of South Asia: A high literacy rate (near universal literacy in the case of the youth); and almost universal electrification. Notably, poverty is not as rampant as in rest of South Asia, thanks to a large diaspora, especially in Britain. Likewise, the left has been surprisingly successful in establishing itself as a leading force on campus.

Not merely two former prime ministers but many mainstream politicians started their political careers on the platform of the staunchly-Marxist student outfit, the National Students Federation (NSF). The NSF, over the years, has split into two main factions (one faction embracing Trotskyist ideas) but maintains a strong base in extra-parliamentary politics.

Interestingly, the PaJK electorate votes for parties that collaborate with Islamabad. After all, the leftwingers can neither contest elections nor do they stand a chance of winning, since elections are rigged in a thousand ways. However, agitation is organised from the platform of left-wing and secular-nationalist parties. This is an observable pattern since the 1990s.

A similar dynamic was visible in the summer this year, too, when the traders joined the Rawalakot sit-in. In collaboration with Rawalakot-based left and secular-nationalists, a Peoples Action Committee was formed. A charter was hammered out and the key demands mentioned above were adopted.

Centrality of electricity prices

Pakistan’s second largest hydro-power project, Mangla Dam, lies in PaJK (check?). A few other key hydro-power projects, with Chinese investment, are under construction. Through these projects, Pakistan generates more than 3000 mega-watts of energy, while local consumption is merely 400 mega-watts.

Moreover, Pakistan is supposed to pay PaJK a royalty — worth billions of rupees annually — which has been denied. While the parliament and the puppet regime in PaJK’s capital Muzaffarabad stay silent on such justified concerns, the left and the nationalists vociferously agitate to press the demand for royalty payments.

Despite better living standards compared to a majority in Pakistan, a lack of job opportunities increasingly worries PaJK, which is experiencing a youth bulge. “If Pakistan would only pay the royalty on Mangla Dam, our state would transform,” is a common refrain heard across PaJK, even before the current uprising. It is, therefore, understandable that there are ongoing mobilisations against inflated electricity bills.

Once the traders joined the Rawalakot dharna, familiar police methods were deployed. However, when police evicted protesters, this led to street agitation. Within two days, the dharna resumed, the eviction popularising its demands.

Seizing the opportunity, a call not to pay electricity bills was issued by sit-in planners. It gained currency. Hence, as the September monthly bill payment deadline approached, the Peoples Action Committees — which were popping up across PaJK — appealed to consumers to submit their bills to the local branch of the Committee instead of submitting them to the electricity department. Gathered in their millions, these bills were set on fire. In certain places, climate-friendly leaderships advised people to destroy the bills instead of burning them.

By October, the boycott extended, with more and more consumers joining in. In response, more than 50 key activists were arrested, while the authorities threatened to register anti-terrorism charges against electricity consumers not paying their bills.

These heavy-handed state measures were responded to, on the one hand, by observing a general strike on October 5, and on the other, by extending the agitation. In the next phase, the Peoples Action Committees have announced a mobilization of women on October 10 and students on October 17.

Unsurprisingly, at the time of writing, the government spokespersons have promised talks, while police continue chasing Peoples Action Committee leaders, who have gone underground. Co-author Harris Qadeer is also in hiding to evade arrest. The police, simultaneously, are hesitant to detain activists because police stations where activists are detained are besieged by unarmed agitators. Besides being sympathetic to the demands, the cops don’t want “picket lines” outside their stations. In one case, police were forced to release arrested activists just hours after they were detained.

Meanwhile, the mainstream Pakistani media are avoiding any coverage of the movement. Despite this, Pakistan has also been infected. In certain towns, Peoples Action Committees have been set up, while traders associations in Karachi, the metropolitan hub of the country’s trade, have threatened not to pay their electricity bills. The situation in Pakistan is already explosive. An intifada against years of neoliberal “reforms” is the only option left to roll back the International Monetary Fund-dictated agenda that has pushed millions of lives into misery.

[Harris Qadeer is Rawalakot-based journalist. He works as a staff reporter for daily Jeddojehad.com, an Urdu-language socialist website. Farooq Sulehria is a leftist writer and academic based in Pakistan.]