By Emilio Poliak

“…I shall be merciless; expiation shall be complete and justice inflexible…The ground will be covered with their bodies; that horrific sight will serve as a lesson.” With those words, Louis Adolphe Thiers – head of the executive of the French Third Republic—announced the defeat of the Commune. Nearly 30 000 Parisians murdered, some 40,000 arrested – many of them were later executed – and thousands were banished or sentenced to forced labor. This way, the French bourgeoisie punished the audacity of the people that for the first time showed that the working class could take power into their own hands and bear a new social order.

The Franco-Prussian war and the revolution

In 1870, under the leadership of chancellor Otto Von Bismarck, Prussia was moving towards German unification threatening the French hegemony in Europe. On July 15th the empire of Louis Bonaparte (Napoleon III) declared war, but the adventure did not last long. On September 2nd, Napoleon III was defeated and taken prisoner together with more than 100,000 soldiers.

On September 4th, massive mobilizations in Paris overthrow the empire and force the proclamation of the Republic. A National Defense government is created, but in reality it hinders and abandons all defense of Paris. The Prussians lay sieged to the capital for four months.

The government only sought peace negotiations. On January 28th, 1871, the surrender of the city is decided. Bismarck agrees on a truce to call for elections for a National Assembly that ratifies the conditions imposed by Prussia: the disarmament of the army of Paris, the payment of a millionaire compensation and the relinquishment to Germany of the cities of Alsace and Lorraine. The more reactionary sectors win the elections and Thiers is appointed chief of the executive power of the French Third Republic. The new government settled in the city of Versailles, a few kilometers from the capital. Their main goal consisted in disarming the Parisian people.

The insurrection

The Parisian resistance was commanded by the National Guard, a different body of the regular army comprised of the armed population and which officials were selected by the battalions. On March 16th, Thiers arrives in Paris with the goal of disarming the people. During the early morning of the 18th, the army tried to seize the canons of the National Guard. The working class took to the streets with women at the forefront. In a few hours, the workers won many soldiers for their cause and expelled the rest. At night, the Central Committee of the National Guard, comprised of delegates of the battalions, were the only authority in Paris after the escape of the government and the bourgeoisie.

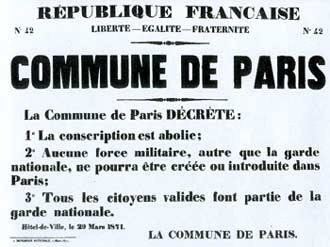

The first measure of the Central Committee was to call for elections to choose representatives in all the districts of Paris. The result of these elections were the rise of the Commune, the members of which were almost all workers or representatives acknowledged by them. Thus, the first government of the workers was born.

The Commune in power

The Commune encompassed legislative and executive functions. All the administrative, judicial and educative charges were elective, revocable and earned the same salary as the rest of the workers.

During the two months it lasted, in spite of the economic crisis on the one hand and the war against Versailles on the other, the Commune carried out measures of rupture with the bourgeois regime targeted at creating a new social order at the service of the working class and the oppressed sectors of the people.

It permanently abolished the army by replacing it with the armed people, declaring war on the National Guard as the only armed force. It condoned the housing rent payments and the debt of traders and craftsmen. It decreed the separation of the Church from the State, suppressed all the salaries that were paid to the clergy and declared all assets of the Church as national property.

Marx would say “this was the first revolution in which the working class was openly acknowledged as the only class capable of social initiative, even by the great bulk of the Paris middle class – shopkeepers, tradesmen, merchants – the wealthy capitalist alone excepted.”

The defeat

Not only the French bourgeoisie, but the entirety Europe were terrorized in the face of this new democratic Workers’ State demanding its destruction. During early April, the Versailles offensive to crush the Commune begins. Thiers makes a pact with Bismarck to dispose of 170,000 soldiers, most of them prisoners released by Germany, an “unprecedented fact that in the most tremendous war of modern times the victorious and the defeated army confraternize in the common slaughter of the proletariat (…). Class domination can no longer disguise itself under the national uniform; all national governments are one against the proletariat” (Marx) On May 20th, they succeed in entering Paris and “the bloody week” begins. On May 28th, the Commune is defeated. Mass killings and summary executions continued until mid-June.

The absence of a preconceived plan and the policy of the different ideological currents inside the Commune, with anarchist predominance, are factors that partly explain the hesitations that enabled the victory of the reaction. Engels would argue years later that “It is therefore comprehensible that in the economic sphere much was left undone which, according to our view today, the Commune ought to have done. The hardest thing to understand is certainly the holy awe with which they remained standing respectfully outside the gates of the Bank of France. This was also a serious political mistake. The bank in the hands of the Commune – this would have been worth more than 10,000 hostages. It would have meant the pressure of the whole of the French bourgeoisie on the Versailles government in favor of peace with the Commune.” Another weakness was not going forward with Versailles to overthrow the central government at its weakest – during early March—before Thiers and Bismarck agreed the strengthening of the army. The luck of other uprisings (Lyon, Marseilles, Toulouse, etc.) would have probably been different and the Commune would have not remained isolated.

Lessons from the first Workers’ Government

The two months the Commune lasted were of a rich experience for the global working class. Despite the defeat, it brought important teachings, enriched Marxist theory on the State and prepared the working class and the revolutionaries for struggles to come. Marx writes as a central conclusion that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes” and states that the Commune was “the political form at last discovered under which to work out the economical emancipation of labor.”

That new form at last discovered was comprised of the replacement of the professional army for “the armed people.” The substitution of the institutions of the bourgeois democracy for a direct democracy where all the delegates are revocable, have no privileges and a salary similar to that of a worker. The generalization of the Russian soviets and their development as organizations of the power of the workers and the people 46 years later have their roots on the experience of the communards.

150 years after one of the most heroic exploits of the history of the workers movement, the words of Lenin are still completely relevant: “The cause of the Commune is the social revolution, the cause of the complete political and economic emancipation of the toilers. It is the cause of the proletariat of the whole world. And in this sense it is immortal.”